Your Favourite AI App Will Die

It won't be because it's bad. It'll be because it's optional.

I keep getting the same question: “What’s your consumer AI thesis?” And the honest answer is… I don’t have one yet.

It’s not because I’m not looking. I’ve seen a lot of consumer AI products this year (and liked and used plenty of them) and I still haven’t found a single one I can hold with conviction through the next few platform releases. The demos are strong. The teams are sharp. And yet my brain keeps doing the same thing: it simulates the next OpenAI/Anthropic update and asks, “Okay, what survives?”

The best way I can describe the feeling is: this is the new version of “what if Google makes this?” except the iteration cycle is so fast that it’s stopped being a distant platform risk and started being a near-term product risk. It’s not “someday they’ll copy you.” It’s “they’ll ship something adjacent in the next few quarters and it’ll land in a surface with hundreds of millions of users.” That compresses the time window in which standalone consumer apps can become defaults. And in consumer, the only real moat is being the default.

So I’m writing this as a confession and a working framework. A heuristic I’m using to filter “cool app” from “durable company” in a market where features get commoditized on contact. This is still WIP. But I’d rather have a WIP filter that keeps me honest than fake certainty that gets me attached to the wrong kind of product.

The Threat Model

Here’s what’s forcing the bar to move.

The old platform risk was “Google will copy your app.” That threat took years to materialise. You’d notice them watching, then they’d clone a feature, then they’d slowly starve you out through distribution. You had time.

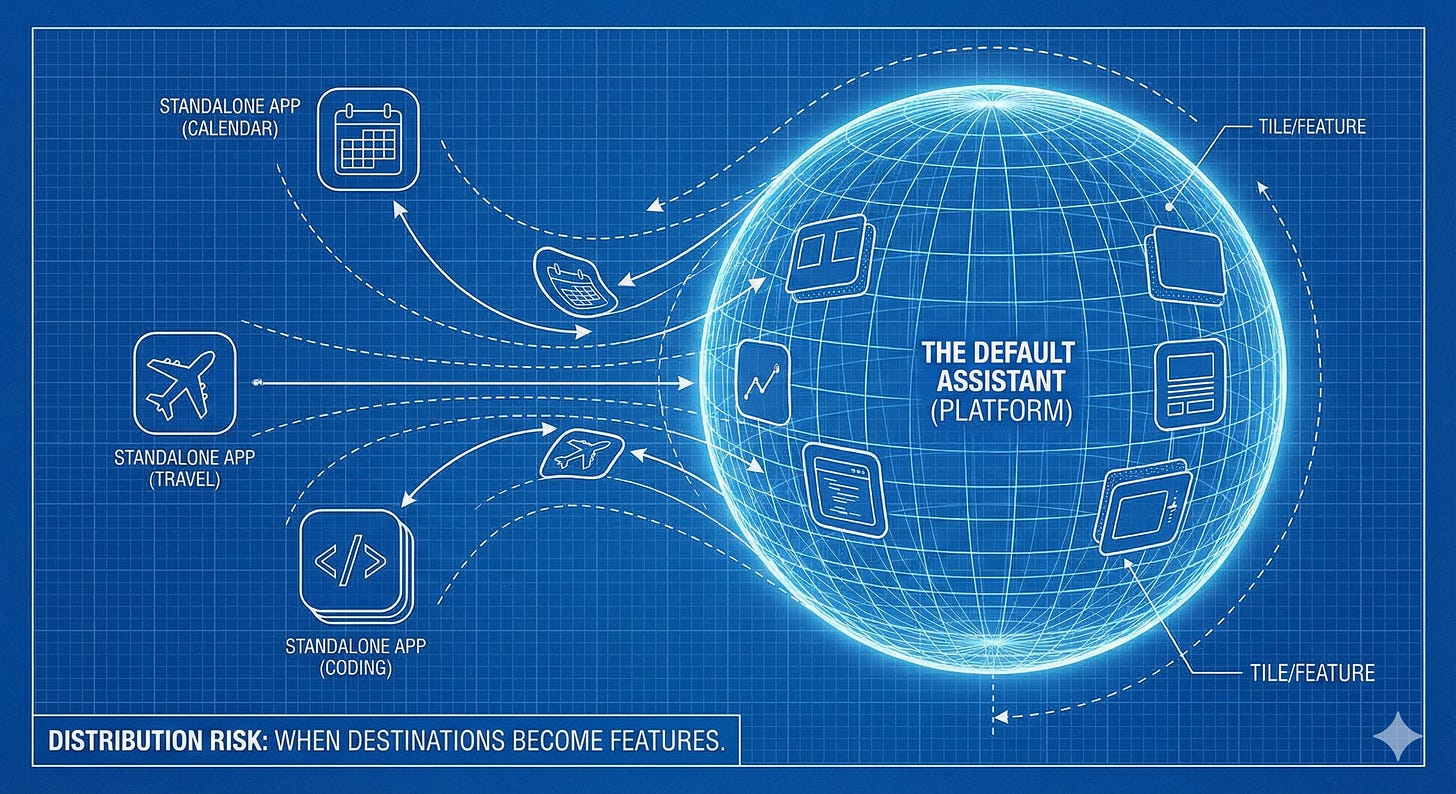

The new platform risk is faster and more structural. The assistants (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) are becoming the starting surface for how people use the internet. And once that happens, whole categories don’t get copied in the old sense. They get reclassified. What used to be a standalone product becomes “a thing you can do inside the assistant.” The moment your category becomes an in-assistant capability, your product stops being a destination and starts being a choice. In consumer, being a choice is often the beginning of the end.

You can see the platform direction in plain sight. OpenAI is building a platform layer inside ChatGPT that treats third-party functionality as first-class. It introduced “apps in ChatGPT” and an Apps SDK, moving those apps into an internal directory where users browse, search, and run them without leaving the assistant.The assistant becomes the hub, everything else becomes a module.

This is what I mean by “default interface.” In the old internet, you started with a browser and went somewhere. In the assistant-native internet, you start with a prompt and the somewhere is optional. The assistant can answer, fetch, generate, and increasingly act through apps. When you can order food, build a playlist, pull files, or perform a workflow as an in-surface action, the user’s baseline changes from “open my app” to “ask the assistant.” The user doesn’t decide to use your product. The assistant decides whether to route to it.

And the platforms are actively closing distribution escape hatches. WhatsApp is the most brutal example. Meta’s WhatsApp Business API policy changes mean general-purpose assistant-style chatbots are expected to be blocked from operating via WhatsApp after January 15, 2026, specifically the kind of open-ended “ask me anything” bots people were using to access ChatGPT or Copilot inside WhatsApp. If your consumer wedge was “we’ll live inside messaging,” that’s a reminder that you don’t own that surface.

So the threat model has two reinforcing layers. First: product bundling. The assistant expands from “answer box” to “action hub” via apps, directories, SDKs, and native modes, turning entire standalone categories into in-surface features. Second: distribution control. Even if you find a surface where users already are, the platform can change policy and decide what kind of bot is allowed to exist there.

This is why “we’re building a better flow” is such a fragile consumer AI pitch right now. The flow itself is not scarce. The model is a commodity substrate. The workflow logic is increasingly replicable. And the distribution advantage belongs to whoever controls the starting surface. When all three are true, the standalone app has to answer a more foundational question: why does this workflow deserve its own destination, rather than becoming a built-in capability of the default interface?

A lot of good consumer AI products are going to die for reasons that will feel unfair to their builders. They won’t die because they’re bad. They’ll die because they’re optional, and optional products get murdered by defaults. It’s the same story as browser toolbars and early mobile utilities and a thousand other consumer patterns, except the loop is faster now because the platform can ship new behavior weekly and instantly place it in front of a massive installed base.

So when I say I’m struggling to form conviction, this is what I mean. I’m not struggling to find products that work. I’m struggling to find products whose value doesn’t get reclassified into “a thing the assistant can do” the moment the platform decides it should.

The New Bar: “What Stays True After the Clone?”

I now try to evaluate every consumer AI product as if the platform has already shipped the clone.

What if the assistant gets a new native mode that covers seventy percent of what you do? What if the user can do the thing without leaving the default surface? What if the novelty spike that helped you acquire disappears because the baseline moved? After that happens, what remains true?

That’s the question. Not “is this impressive.” Not “would I use it.” Not “does it have a billion-dollar market.” What remains true after the platform ships the adjacent capability and makes it a default?

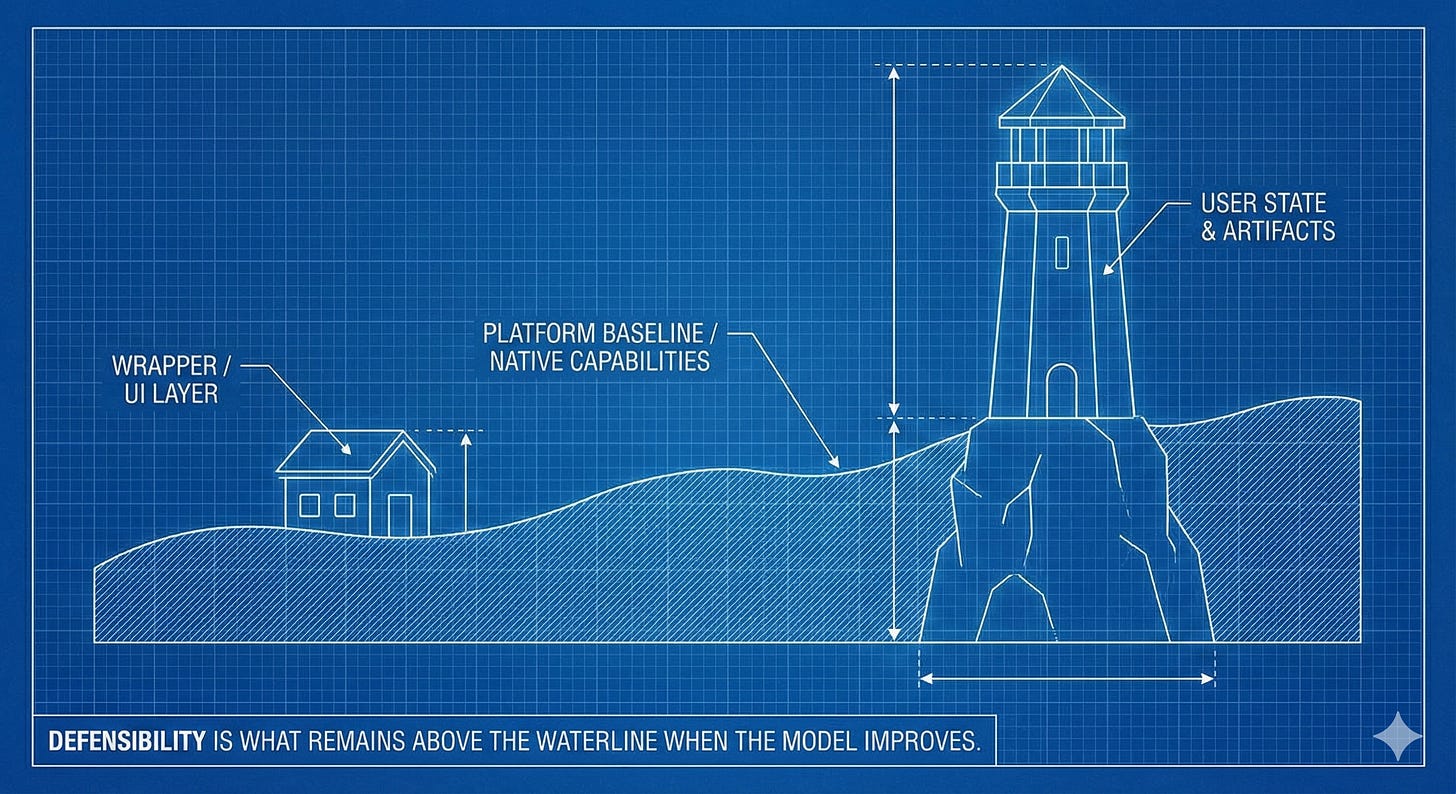

We keep mistaking differentiation for defensibility. We confuse “we’re better” with “we’re hard to replace.” In a market where the substrate improves weekly, “we’re better” is a temporary state. It might even be a short-lived one. Defensibility has to be something that doesn’t evaporate when the substrate gets cheaper, more capable, and more integrated. This is why “we’ll ship faster” keeps sounding weak to me as a moat argument. Speed only works when you’re racing another team with comparable distribution and comparable defaults. In consumer AI, you’re racing an entity that can change the baseline for everyone just by shipping inside the starting surface.

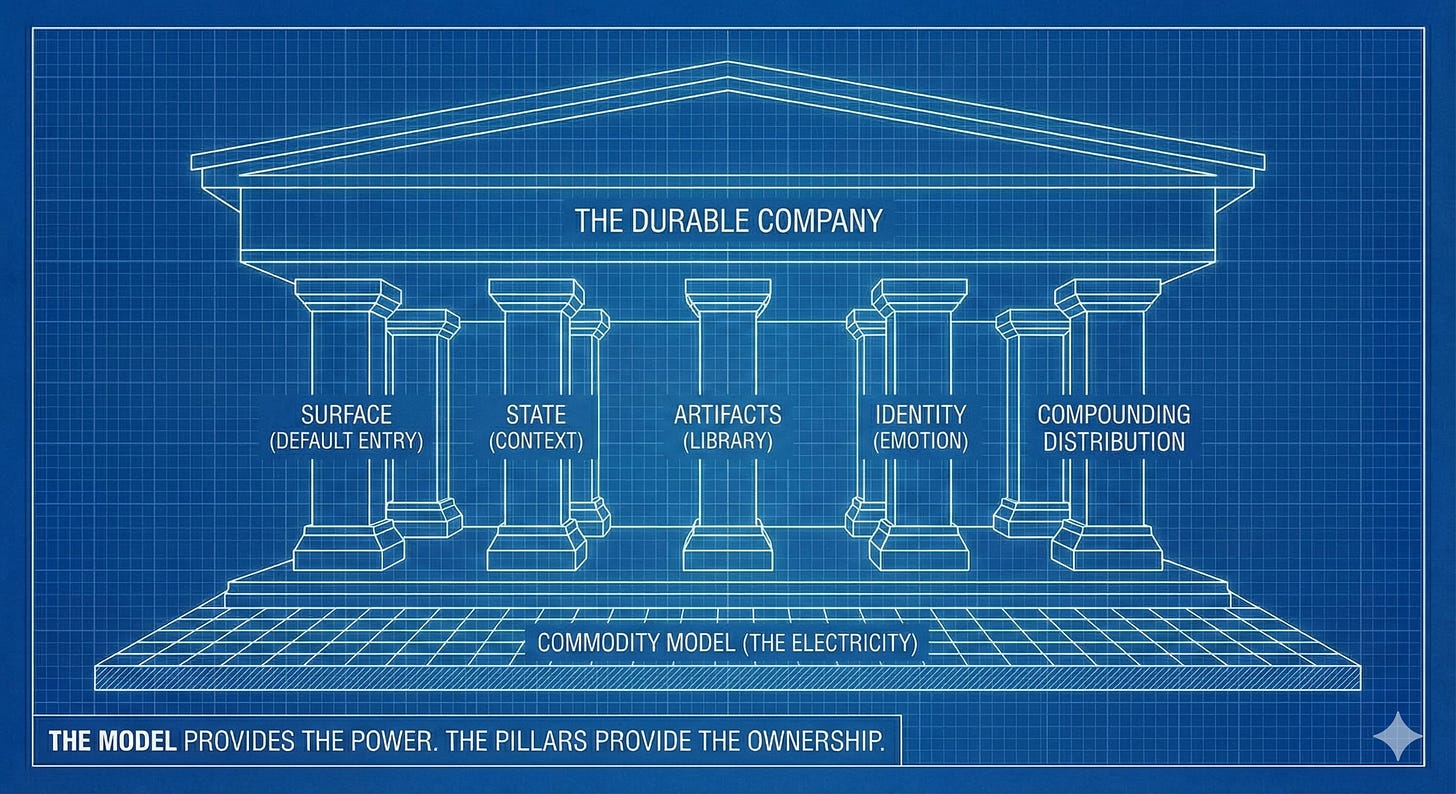

In consumer AI, the model is not the product. The model is the commodity substrate, the electricity. It will continue to improve and diffuse and show up inside everything. You can’t build a consumer moat on the assumption that your model access will be uniquely powerful forever. So when someone pitches me “we’re the best model for X,” I translate it to: “for the next few months, we’ll have an advantage in quality.” That might be enough to get started. It is not enough to justify conviction.

The product is what you own around the model. The part that compounds even if the model becomes interchangeable. The part that stays sticky even if the assistant ships a new native workflow.

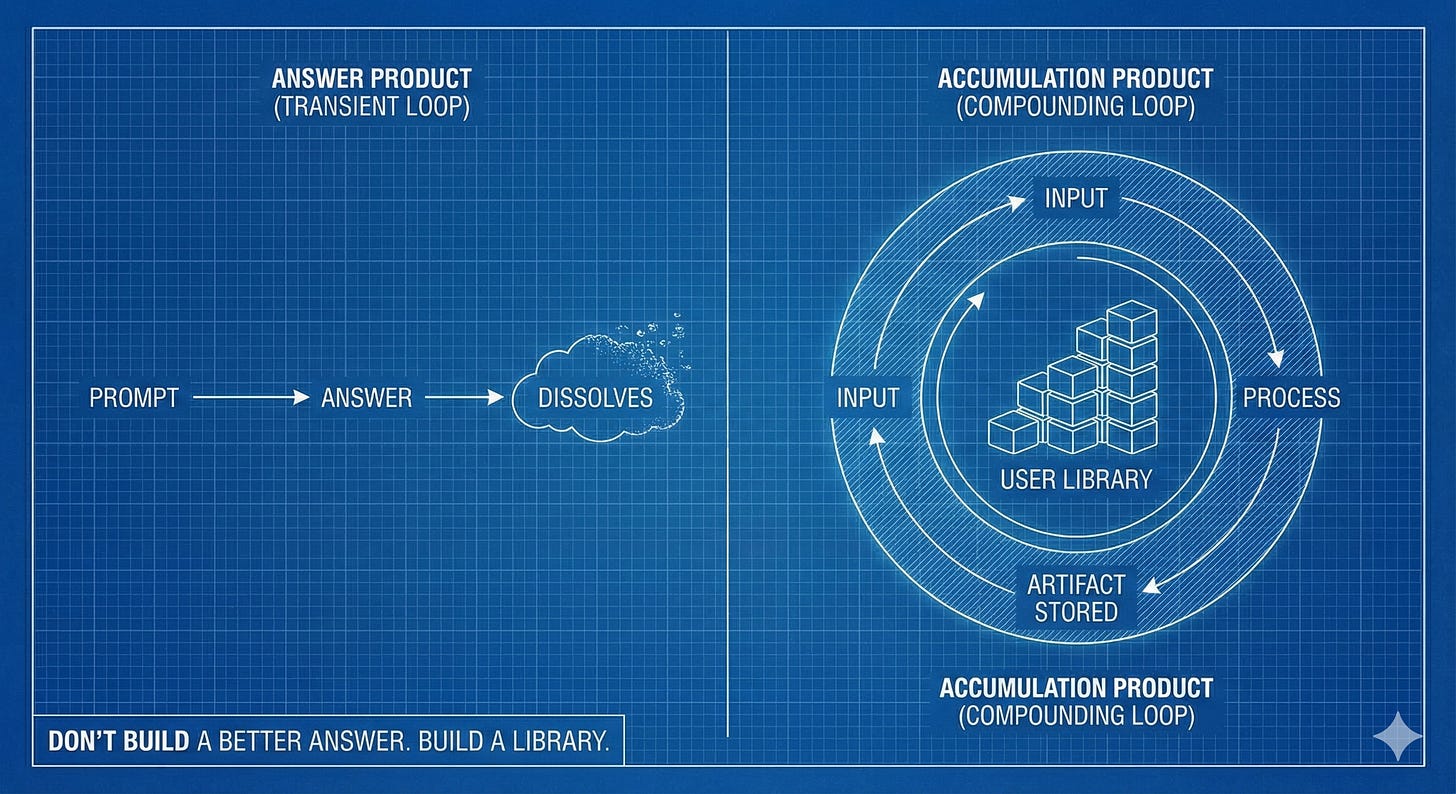

This is where consumer AI splits into two species. The first is the “answer product,” an interface that helps you get a response. Ask → answer → done. Those products can grow quickly because conversion is easy. They can also die quickly because nothing accumulates.

The second is the “accumulation product.” It doesn’t just answer. It captures, stores, organizes, and builds up a user’s life into a structured state and artifacts. It’s a place, not a moment. These products don’t win because the model is smarter. They win because leaving becomes annoying.

If you want to sanity-check which one you’re looking at, don’t look at the demo. Look at what’s left behind after a week of use. Is there anything valuable sitting inside the product that makes it easier to continue than to start over somewhere else? Is there a growing “mine-ness” to the experience?

If the answer is no, the product is betting its entire future on being a better prompt wrapper. And prompt wrappers are exactly what platforms are designed to absorb.

What You Actually Have to Own

Once you accept that the model is the commodity substrate, the “consumer moat” conversation stops being about intelligence and starts being about ownership. Not ownership in the abstract “we own the customer relationship” way that every deck says. Ownership in the literal sense: what part of the user’s behavior do you control, what part of their life do you accumulate, and what part of the distribution path is actually yours versus rented.

The only answers I’ve found that don’t collapse under scrutiny fall into five buckets.

Surface. In consumer, where the user starts is destiny. If the user has to remember to open your app, you’re already at a disadvantage, not because your app is bad, but because consumer behavior isn’t a courtroom. People don’t reward the best argument. They reward the default. The products that feel defensible tend to sit on a surface the user already touches constantly: the keyboard, the camera, the inbox, the browser, the creation canvas, the OS defaults. If you don’t own a surface like that, you need something that acts like one, a channel where you are the default entry point, not a nice-to-have destination.

A fragile product is an app you open when you remember it exists. A more inevitable product is a layer you trip over daily because it’s attached to a behavior you can’t avoid.

State. A lot of consumer AI products feel like they’re building “memory,” but most of that memory is just elevated chat logs. The default assistants are also moving toward memory, so the bar has to be higher: are you accumulating state that is structured and actionable, and does it meaningfully change what the product does?

There’s a world of difference between “it remembers I like Korean food” and “it knows my dietary constraints, my weekly routine, the meals I’ve already cooked, what ingredients I have at home, what I’m trying to optimize for, and it turns that into a plan that gets executed inside my life.” The first can be copied. The second requires a system, a living model of the user that’s more like a graph than a transcript.

State becomes defensible when it’s coupled to action. If your “state” can be exported and imported without loss, it’s not really state. It’s a file.

Artifacts. Consumer users don’t stay because you’re smarter. They stay because their stuff is there.

Think about why people stayed on early creation tools, not because the tools were magical, but because the documents, drafts, designs, playlists, and project histories accumulated. The product became the home for work that mattered. Leaving meant losing the library.

In AI, artifacts are what turn “useful” into “sticky.” A product that generates outputs and lets them disappear is training users to churn. A product that turns outputs into a library (templates you’ve built, styles you’ve refined, collections you’ve curated, a record of what you’ve made) creates switching costs that have nothing to do with model quality.

You can see the failure mode in “AI apps” that are basically disposable output machines. They make something cool. You screenshot it. You share it. You never return because there’s nothing accumulating. The product is a moment, not a place.

Contrast that with products where leaving feels like moving houses. If you’ve built up a library of templates, saved work, personal presets, an evolving body of projects, the product doesn’t need to be the smartest brain. It needs to be the safest home for what you’ve made.

Identity. When capability converges, consumer choice becomes emotional. People pick what feels like them.

This isn’t “brand” in the billboard sense. It’s the product’s personality: its defaults, its tone, the way it responds, the implicit worldview baked into its choices. Some products become the calm one, the professional one, the private one, the one that feels safe for your weird 2am thoughts. Once a user adopts a tool emotionally, switching stops being a rational decision. They don’t shop for alternatives. They stop looking.

This is also why general-purpose assistants are both powerful and limited. They can’t be everything to everyone and also feel intimate to someone. They can’t be universally acceptable and also be deeply identity-aligned for a niche. The products that win on identity offer a relationship with the user’s self-concept and that’s hard to replicate at platform scale without sanding off the edges that made it feel personal in the first place.

Identity moats often live in territory the big platforms will approach cautiously. The more intimate your product becomes, the more it pulls you into questions about emotional reliance, vulnerable users, and content the platforms don’t want their default interface answering at scale. “Shouldn’t” can be a moat, when it’s paired with responsible product design.

Compounding Distribution. In consumer AI, acquisition is not the hard part. Novelty acquires. The hard part is staying power. A lot of consumer AI companies look like they’re winning because they can buy users cheaply or go viral for a week. Then churn arrives and you realize you weren’t building a business; you were surfing a X trend.

The only distribution that matters long-term is distribution baked into the product’s outputs and behaviors. Social loops where creation leads to sharing, and sharing leads to new users. Collaboration loops where teams, couples, friend groups pull each other in and create retention through coordination. Community loops where belonging creates both acquisition and stickiness. Embedded loops where the product reappears without you begging for attention, because it’s integrated into the workflow. Content loops where the product naturally generates things that are searchable, discoverable, and continuously bring in new demand.

If the distribution plan is “we’ll run ads,” I treat that like a warning. It can work in stable categories where retention is genuinely high and the market doesn’t get commoditized weekly. In consumer AI, if you’re paying for attention without a compounding loop, you’re funding an experiment that may never settle into habit before the baseline shifts again.

You don’t need all five. Most products won’t. But you need at least one to be unreasonably strong, and ideally two reinforcing each other. Surface plus state is powerful. Artifacts plus identity is powerful. The fragile products are the ones that have none of these and are trying to live entirely on “we’re a better answer box.”

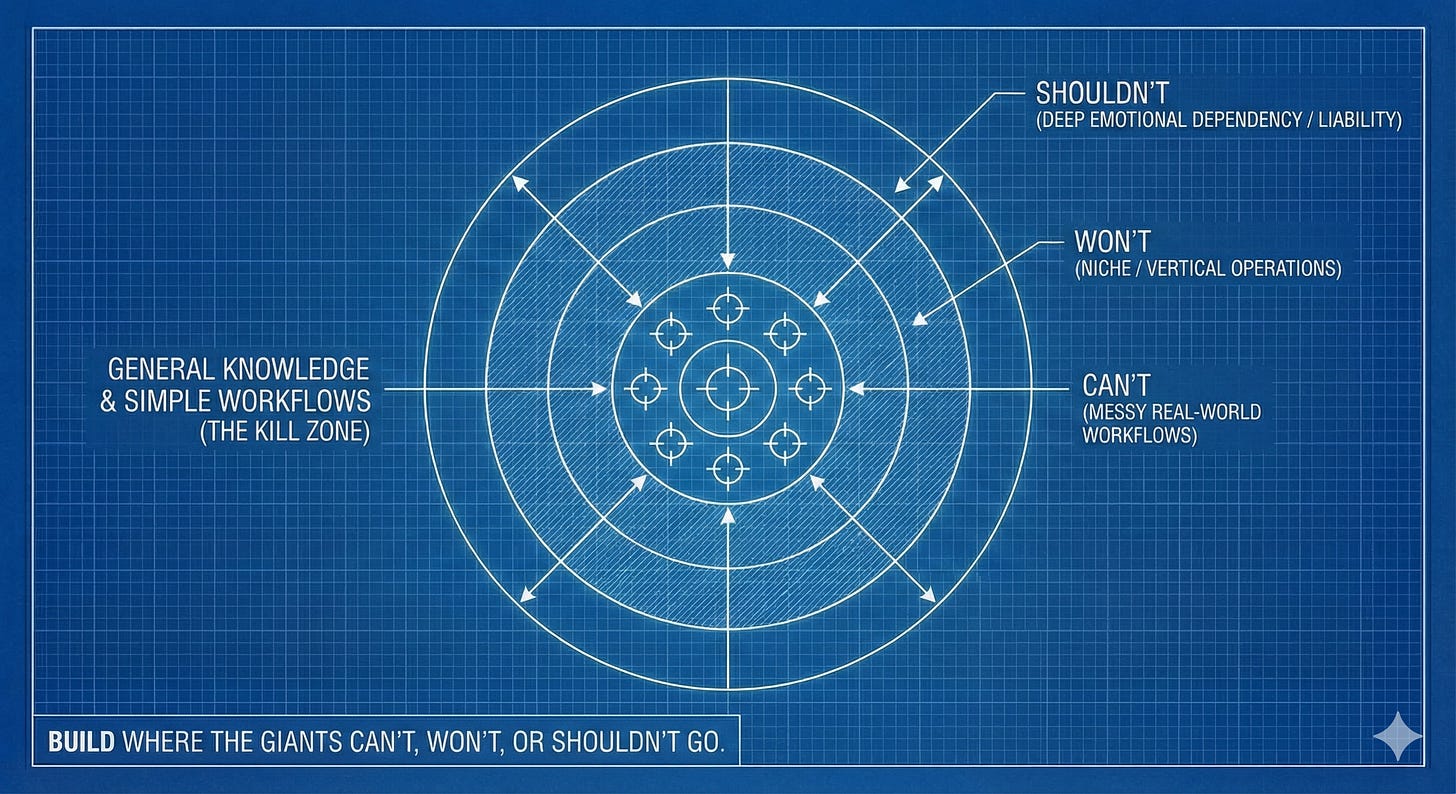

The North Star: Build What They Can’t, Won’t, or Shouldn’t Build

Even if you nail product craft, even if retention is decent, even if you find a wedge, you can still get deleted by a platform move that isn’t even hostile. It’s just the platform doing what platforms do, expanding the default interface and reclassifying behaviors. If you accept that as baseline, the goal shifts. You stop trying to build something they could build better eventually, and you start trying to build something they either can’t, won’t, or shouldn’t build.

“Can’t” is where most people overestimate themselves. Everyone says “they can’t do this because we have domain expertise,” and then you look closer and the “domain expertise” is basically a curated prompt and a nicer UI. That’s not a can’t. That’s a not-yet. A real “can’t” usually comes from ownership of non-linear, real-world workflow and state- stuff that’s annoying to integrate, hard to maintain, and deeply specific.

“Won’t” is less about technical difficulty and more about incentives. The platforms are chasing massive, horizontal markets. They’ll build the general version of everything. But they’re often unwilling to build very specific, operational, niche products because it fragments the experience and complicates positioning. This is where “small market” can actually be a feature if the market is small to them but large enough for you, and if the workflow is frequent enough to create habit and accumulation.

“Shouldn’t” is going to matter more than people are comfortable admitting. There are product categories that big platforms will approach cautiously because the reputational downside is asymmetric. Companion experiences are the obvious one: they can be incredibly sticky, but they pull you into questions around emotional reliance, minors, and safety. When you’re the default interface, you don’t get to be edgy with intimacy at scale without backlash.

The entire AI companion space has been pulled into public scrutiny. Character.AI has faced heavy criticism and legal pressure; Replika has faced allegations around targeting vulnerable users. From an investing lens, if you want to build a companion product, you cannot be naive about safety posture. You’re not shipping “engagement.” You’re shipping a relationship simulator. The best companion companies will look less like growth hacks and more like trust-and-safety companies with a kinky product layer.

The Humane story is also instructive here, not because hardware is inherently doomed, but because it’s a blunt reminder that “new surface” bets are unbelievably hard when you don’t achieve default status fast enough. Humane’s AI Pin shutting down and being sold off to HP is the extreme edge of consumer surface risk: if you don’t own distribution and you don’t become inevitable, the market doesn’t give you time to iterate into inevitability. Consumer doesn’t reward ambition. It rewards being where people already are, or becoming the place they can’t stop returning to.

Three Archetypes That Can Survive Bundling

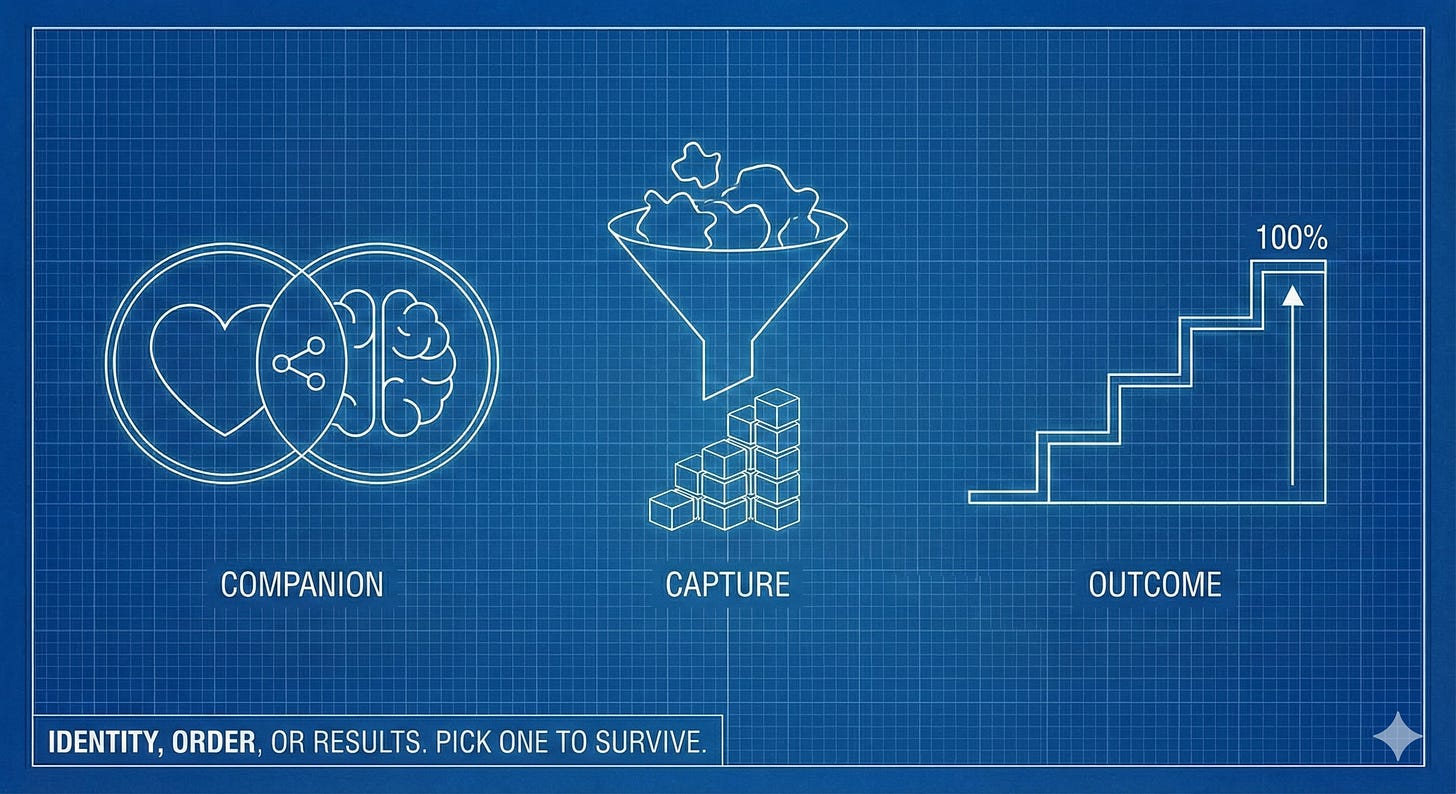

When I compress this into something I can actually use on a random Tuesday when a founder sends me a deck, I keep coming back to three shapes.

Companion / Identity Products

This is the archetype that looks frivolous to “serious people” right up until you see the retention curve. It’s not an assistant. It’s a relationship-shaped product: a personality, a ritual, a place where the user is outsourcing company, reflection, affirmation, even intimacy. If you build this well, you don’t compete on raw capability; you compete on attachment. The user doesn’t come because the model is smartest. They come because the product feels like theirs, and because the interaction sits close to identity and emotional routine, the same psychological territory where switching costs are irrational.

This is both the most defensible and the most dangerous archetype. The big platforms can absolutely build companions technically. The reason I think this can be a “shouldn’t” moat is that doing it at scale drags a general-purpose brand into a risk profile it doesn’t want. When you’re the default interface, you don’t get to play fast and loose with intimacy, minors, mental health, and emotional dependency without attracting regulatory heat and reputational blowback.

From an investing lens, this archetype forces a very specific kind of seriousness. If you want to build a companion product, you cannot be naive about safety posture, age gating, moderation, and what you’re optimizing for. You’re not shipping “engagement.” You’re shipping a relationship simulator. The opportunity is real because relationships are sticky, but the failure mode is not “churn,” it’s backlash.

Capture Products

Less sexy in conversation but far more structurally sound. You own an input surface or a capture habit, camera, voice, keyboard, clipboard, screenshots, notes, receipts, and you use AI to turn scattered reality into structured state and artifacts. The product isn’t “answers.” It’s the pipeline from messy life to organised memory, plus the downstream outputs that become a library.

A food-tracking app that uses your camera to log meals and builds a structured picture of your diet. A voice-notes app that transcribes, tags, and organises your thoughts into a searchable second brain. A receipts app that photographs purchases and turns them into categorised spending data. These capture systems where your life accumulates, and leaving means losing the record.

The archetype extends into creation tools when the creation surface itself becomes the capture layer. Canva’s direction with Magic Studio is instructive: AI features embedded across the visual creation surface, so the user’s behaviour is not “go ask an assistant” but “make the thing where I always make things.” The user’s designs, templates, brand kits, and project history accumulate inside Canva. AI accelerates what they’re already doing, inside a home they already own. That’s capture-as-creation: the product becomes the place where work lives, not a momentary tool you visit.

The obvious pushback: can’t the default assistants also become capture tools? They can try. But capture is harder to bundle cleanly because it’s not just “generate.” It’s permissioning, integration, storage, organisation, retrieval, collaboration, export, and reliability across months. It’s the boring bits of plumbing that make state real. The assistant can do a lot in a single session. It’s much harder for it to become your system of record without becoming bloated, brittle, or invasive.

Outcome Products

This is where you pick a specific high-frequency behavior and you win by producing a measurable result reliably, and not just by sounding smart. It’s less “talk to me” and more “get me to the finish line.” The best outcome products are almost anti-chat. They take the model and hide it inside a workflow that ends in something you can count: lessons completed, workouts done, money saved, leads generated, habits built, language fluency improved.

Duolingo is a good example of what outcome-native looks like in an AI era. Duolingo Max added features like “Explain My Answer” and “Roleplay” powered by OpenAI, but the product is still fundamentally an outcome engine: it’s built around streaks, progression, lessons, and habit formation. The AI is not the product. The product is the system that keeps you showing up, measures your progress, and makes leaving costly because your history and momentum live there. The assistant can roleplay with you too, but it doesn’t automatically give you the architecture that turns practice into adherence over months. Outcome products win by owning the loop, not by owning the best model.

This archetype is also where a lot of “better ChatGPT for X” companies should probably evolve if they want to survive. If your thing is studying, don’t be an answer box, be a measurable study system. If your thing is fitness, don’t be a plan generator, be the place where workouts are executed, logged, adapted, and reviewed. If your thing is travel, don’t be an itinerary writer, be the place where bookings happen, updates land, preferences accumulate, and trips become a library.

I think Outcome might actually be the most underrated of the three archetypes. Companion gets all the thinkpiece attention because it’s provocative. Capture gets respect because it sounds like SaaS. But Outcome products, where intelligence is hidden inside a loop that produces measurable results, might be the most defensible because they’re the hardest to unbundle back into a chat interface. Duolingo works precisely because you don’t want to “chat with an AI about Spanish.” You want to complete the lesson, extend the streak, see the progress bar move. That loop ownership is genuinely hard to replicate in a general-purpose assistant.

So when I look at consumer AI now, these are the three shapes I’m pattern-matching for. Companion is identity-first and survives via attachment, but it comes with serious trust and safety obligations, and it may benefit from the fact that big platforms “shouldn’t” go all the way there at scale. Capture is habit-first and survives via state and artifacts, because it becomes the home for a user’s life or work and leaving is logistical pain. Outcome is result-first and survives via loop ownership, because it turns intelligence into adherence and measurable progress rather than clever conversation.

Everything that’s basically “better ChatGPT for X” is guilty until proven innocent. If your product is a nicer answer box, your destiny is to become either

a tile inside the default assistant’s surface, or

a churn machine that lives off novelty until the baseline catches up. You can still build a business in either scenario, but you’re not building a moat.

The Scorecard

When I’m trying to decide whether something is a company or a very well-designed demo, I can’t stay in theory. Theory makes everything sound plausible. You can defend anything with enough adjectives. So I force myself into a scorecard that’s deliberately hostile to “but the UX is nicer.” It assumes the platform is going to keep expanding its default surface. It assumes distribution can be taken away overnight if you’re building on someone else’s rails. It assumes that “we’ll ship faster” is a tactic, not protection, because the platform can ship slower than you and still win if it ships to the starting surface with a built-in distribution advantage.

These are the fifteen questions I now try to answer before I let myself feel excited. If a product can’t survive fifteen minutes of honest interrogation, it definitely won’t survive the next platform cycle.

Surface & Distribution

Where does the user start their day, and are you already there, or are you asking them to remember you exist?

If you removed all paid marketing tomorrow, what organic loop would still bring new users next month?

What happens to your product if the platform you’re distributed through (App Store, WhatsApp, the ChatGPT plugin directory) changes its policies or buries you?

Is your distribution channel one where you set the rules, or one where you’re a tenant who can be evicted?

Does using your product naturally create something shareable, searchable, or referable that brings in new users without you asking?

State & Artifacts

What’s left behind after a week of use, and would migrating it to a competitor feel like moving houses or exporting a spreadsheet?

Is your “memory” actually structured state that changes outcomes, or is it just chat logs with a longer context window?

Do artifacts accumulate inside your product in a way that makes the next session easier, faster, or more personalized than the first?

If a user asked to export everything and take it elsewhere, how much would break or become useless outside your system?

Does your product get meaningfully better for the individual user over three months? Not through model improvements, but through accumulated personal context?

Defensibility & Moat

If the foundation model company ships seventy percent of your functionality as a native mode next quarter, why do users still come to you? What remains uniquely true?

Is your defensibility based on something you’ve built, or on something the platforms haven’t gotten around to yet?

Which part of your product sits in the “can’t / won’t / shouldn’t” zone for the model vendors, and is that a durable position or a temporary gap?

What would it cost OpenAI or Anthropic in focus, complexity, brand risk, or organizational willpower to do what you’re doing, and why would they choose not to?

In three years, if your company is successful, will you have built compounding assets (data, workflows, network effects, trust) or will you still be racing to stay ahead of the next model release?

The scorecard isn’t asking “is the product good?” Plenty of good products fail in consumer because “good” is not the same as “default,” and “default” is the only moat consumer has ever truly respected. It’s asking whether your product is becoming a place where a user’s life accumulates, or whether it’s a moment they visit when they remember.

That difference sounds subtle. It is not subtle in practice. Moment-products live on conversion and novelty and churn. Accumulation-products live on compounding and inertia and “my stuff is here.” The first kind can look like traction in the short term. The second kind is what turns into a business you can hold through turbulence.

I want to be clear about what I’m not saying. I’m not saying consumer AI is uninvestable. I’m not saying every consumer AI company will fail. I’m saying that the old heuristics, ie “great UX + faster shipping + slightly better outputs”, don’t produce conviction in a market where the baseline moves weekly and the default surface is actively trying to swallow workflows. The bar has to move. And the new bar is: does this product stay true even after bundling, because it doesn’t just answer, it accumulates?

So my filter is simple: if the platform ships 70% of your core functionality tomorrow, do users still come to you because they have to, not because they remember to?

If yes, you’re building something real. If no, you’re building a prompt.

And prompts are free.

feels so much more real post yesterdays claude update for nontech users

This is a great roadmap for founders running to build wrappers and not reflecting enough to make it defensible!