You Don’t Need a PM.

You Need a Designer Who Gets It.

There’s a very specific kind of hire that early-stage founders, especially first-timers, tend to make far too early.

And they usually make it for all the wrong reasons.

The product manager.

It sounds reasonable on paper. After all, product is central to a startup’s success, and managing product sounds like something one should, well, manage. But if you’re still in the phase where the company is held together by late-night brainstorming sessions, feedback loops in WhatsApp groups, and a Figma file that everyone knows how to open but only one person dares to touch, you probably don’t need a PM. You need a designer who understands humans, knows enough tech to speak to engineers without a translator, and is comfortable sitting in ambiguity without defaulting to process.

I say this not to diminish the value of product managers in general (they’re crucial at certain stages!) but because I’ve seen too many young startups hire PMs as a sort of emotional outsourcing. Not because the company needs someone to build structure around product development, but because the founder is quietly panicking. And they’re hoping that if someone else owns the roadmap, they won’t have to own the consequences. But here’s the thing: early-stage product development isn’t just about what gets built. It’s about who takes responsibility when it doesn’t work.

And that responsibility, no matter how uncomfortable, remains with the founder.

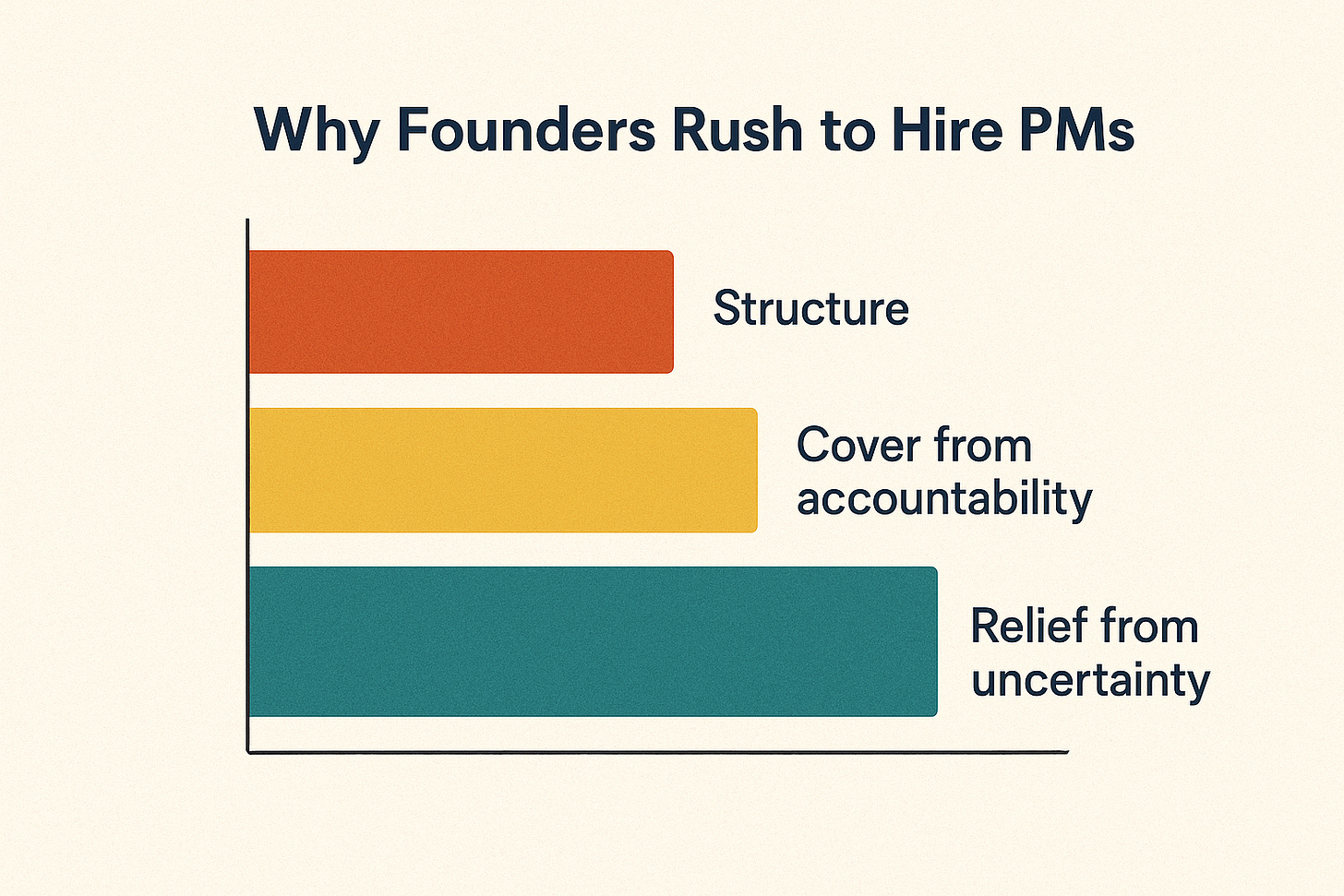

Why Founders Rush to Hire PMs (Even When They Shouldn’t)

Early-stage startups are emotional pressure cookers.

You’re trying to turn a vague but promising idea into something real and repeatable. Every day is a flurry of trade-offs between speed and precision, between ambition and technical constraint, between what users say they want and what they’ll actually use.

It’s exhausting.

And somewhere between the first dozen user interviews and the third product iteration, a seductive thought creeps in: maybe it’s time to bring in a product manager.

At first glance, it makes sense. PMs bring structure, right? They’ll write the specs, manage the backlog, handle the cross-functional chaos, talk to the engineers so you don’t have to. But if you’re being honest with yourself, that’s not really why you’re making the hire. What’s actually happening is that you’re looking for cover. You’re hiring someone so the next time the product fails, or adoption lags, or an investor asks “why isn’t this built yet?”, you can say, “Well, that wasn’t really my call. That was product’s decision.”

This, unfortunately, is a trap.

Because hiring a PM doesn’t transfer ownership. It just adds a layer. You’re still the one people look to when things break. You’re still the one accountable for the company’s direction. You can’t outsource the burden of judgment. And if you try to, you risk creating a power vacuum where your PM can’t act with authority because they don’t have your conviction, and you’re no longer close enough to product to course-correct.

The result is a kind of grey zone where no one is really making decisions, and progress starts to feel like movement without momentum.

What’s worse, your early PM is often set up to fail. They’re hired into a company that hasn’t found product-market fit yet, expected to “own” a product that’s still forming, and they often don’t have the same depth of context that the founder does. Instead of leading, they end up translating: relaying the founder’s instincts into JIRA tickets and trying to bring order to a process that shouldn’t be over-ordered yet.

And when it all goes sideways, they get blamed.

It’s a lose-lose setup born out of a very human impulse: the desire to not feel the full weight of uncertainty alone.

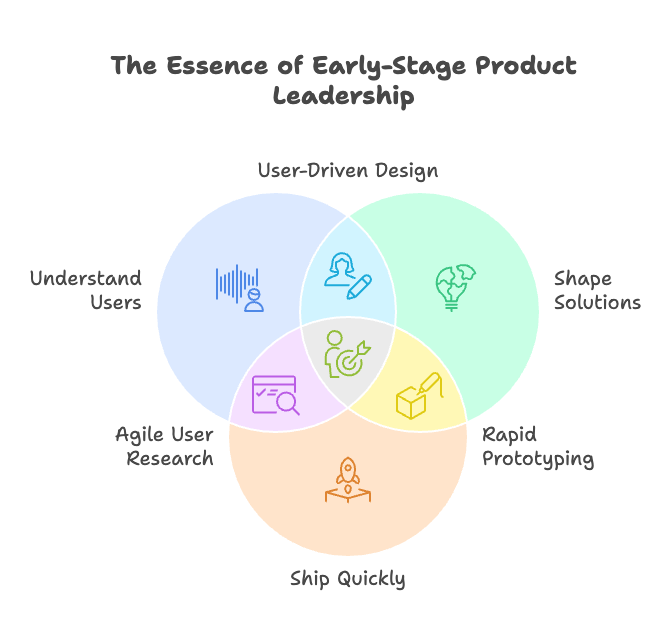

Why Designers Are Better Suited to Early-Stage Chaos

If you’re still figuring out what you’re building, who it’s for, and what they’ll pay for, it’s not process you need. It’s proximity. And designers, the good ones, are experts at getting close to the mess. A great early-stage designer doesn’t wait for a fully scoped ticket or a neatly worded user story. They sit in the discomfort of not knowing. They ask better questions. They sketch things out. They test fast, listen harder, and translate intuition into interface before anyone else can even articulate the problem.

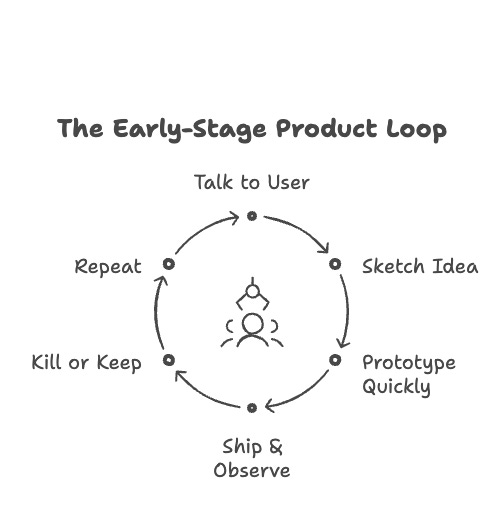

Designers are trained to navigate ambiguity, not just tolerate it, but work with it. They’re pattern recognizers, not checklist followers. While PMs often reach for frameworks and market sizing slides, designers reach for Figma and start exploring. That’s not to say they’re unstructured, far from it. But their structure is user-first, feedback-heavy, and fast-moving. In the earliest stages of a product, you don’t need a 30-item backlog. You need a rough prototype and five users to react to it. Designers do that without blinking.

They’re also naturally multidisciplinary. The best ones speak enough engineering to collaborate directly with devs, enough strategy to frame a customer problem in business terms, and enough empathy to see not just what users do, but why they do it. In a three-person team, that kind of range is priceless. One person who can synthesize user insight, design the solution, and collaborate on implementation? That’s not a nice-to-have, that’s your first product team.

If you're a founder trying to hire your first product collaborator, look for a designer who:

Can speak fluently with engineers and understand feasibility constraints.

Actively asks, “What problem are we solving?” before they open Figma.

Has experience talking to users directly, not just through a research report.

Is comfortable prototyping fast and iterating without handholding.

Thinks in flows, not just screens.

Make this person your co-conspirator. Sit next to them. Co-own the roadmap. Let them challenge you. A designer like this doesn’t just fill a gap, they accelerate your understanding of what to build and how it should feel. That’s the job right now. Everything else can come later.

Apple, Airbnb, and the Case for Design-Led Product Thinking

Let’s look at two companies that didn’t just tolerate design leadership, they built their entire product cultures around it.

At Apple, the product management function doesn’t even sit where you’d expect. Most “PMs” are actually in the marketing org. What drives product? Design and engineering. Human Interface (HI) teams set the tone. Craft, clarity, and conviction take precedence over A/B tests and Jira tickets. Decisions aren’t made via committee. They’re made by people who make: people who build, prototype, obsess over pixels and gestures and sound and light. And importantly, people who are deeply embedded in the user’s experience, not distanced from it by layers of abstraction.

This isn’t some Jobs-era relic. It’s a systemic belief at Apple: that product excellence isn’t project managed into existence. It’s designed. It’s owned. It’s painstakingly, stubbornly made better by people who are close to the user, the material, and the why.

Airbnb took it one step further. In 2023, Brian Chesky collapsed the PM function entirely. He merged product management with product marketing and handed creative control back to design. Why? Because he saw what happens when you over-index on PM-led optimization. You get a roadmap full of small wins, but the soul of the product begins to drift. The team becomes obsessed with iteration and forgets to imagine.

His insight was simple: if you can’t tell a compelling story about what you’re building, you probably shouldn’t build it. So instead of separating product and marketing, Airbnb merged them. Product marketing managers now own both the story and the strategy. Designers shape the vision. The result is a series of bold, cohesive launches that feel opinionated again. Like someone is actually at the wheel.

This isn’t about copy-pasting their org charts into your startup. It’s about recognizing what they optimized for: clarity of vision, closeness to the user, and creative leadership that doesn’t get diluted in layers of middle management.

Ask yourself: if Apple and Airbnb made design, not traditional product management, the core leadership muscle of their most critical product decisions, what’s stopping you?

More specifically:

Can your early team articulate why they’re building each feature, without referring to a spreadsheet?

Do your product decisions feel like they come from proximity to users or from generalized assumptions?

Is your first product hire someone who can tell the story and build the experience, or just track progress?

If the answer to any of these feels off, it’s a sign. Start there.

Founder Mindset: Ownership Over Avoidance

Here’s the uncomfortable truth most early-stage founders eventually run into:

There is no one coming to save you from your own product decisions.

No hire, no process, no clever delegation will fully protect you from the reality that you are the one people look to for direction, and that, until the product works, everything is product.

That doesn’t mean you need to have all the answers. It does mean you need to sit in the questions longer than is comfortable. Because those questions, what do users really need, what pain are we solving, what are we willing to say no to, are not side quests.

They are the work.

And handing them off too early, under the guise of “let the PM handle it,” is one of the fastest ways to lose grip on the thing you’re supposed to be building conviction in.

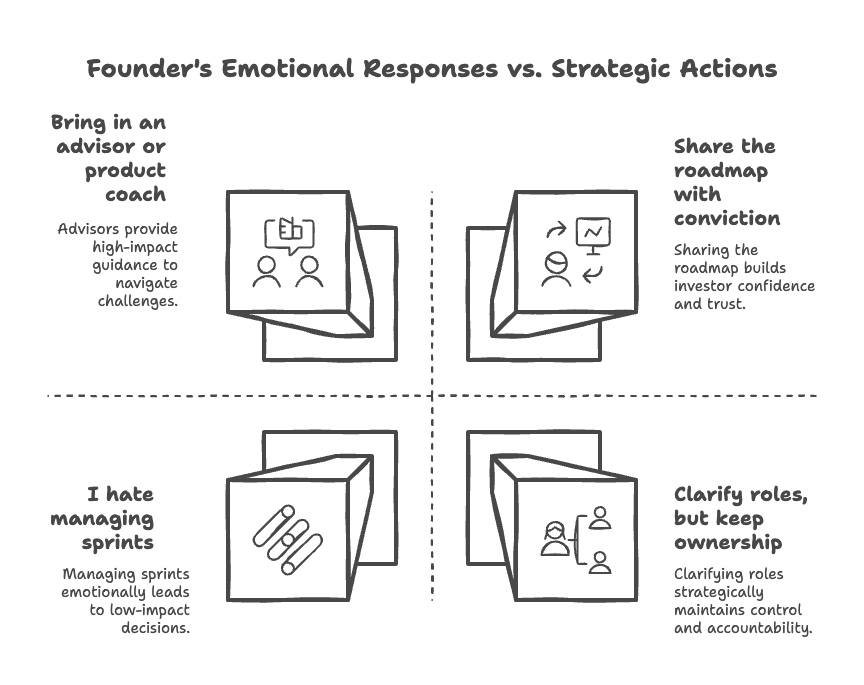

And here’s what most founders won’t admit: hiring a PM too early is often less about operational need and more about emotional relief.

It’s an elegant way to create distance from the pressure. Someone else can run the standups, talk to the users, write the specs. You can focus on “strategy.” But in a company that doesn’t yet know what it is, strategy without product ownership is just vibes.

You’re not leading, you’re hovering.

This isn’t a condemnation. It’s a gentle call-in. You are allowed to be overwhelmed. You are allowed to wish someone else could make the hard calls. But you are not allowed to offload ownership without consequence. Because early teams take cues from the founder. If you outsource clarity, they’ll default to indecision. If you disengage from product, they’ll build what they think you want instead of what the user needs. If you treat product management like a scapegoat, you’ll lose trust before you’ve even built something worth managing.

Check yourself on these:

Are you hiring a PM because you genuinely need roadmap leadership, or because you’re exhausted by feedback loops and need a break?

Do you still feel comfortable explaining what your product is solving, for whom, and why now?

Are your product decisions still founder-led or founder-avoided?

If you're feeling the urge to tap out, consider instead: can you bring in a product-savvy advisor to help you think through decisions, without handing off the reins? Can you partner with your designer more closely, treating them like a co-pilot instead of a contractor? Can you build in more reflection time so you’re not operating entirely from reaction?

Ownership isn’t about doing everything. It’s about staying close enough to the heart of the work that your team knows what beats matter. That’s leadership. And no one else can do that part for you.

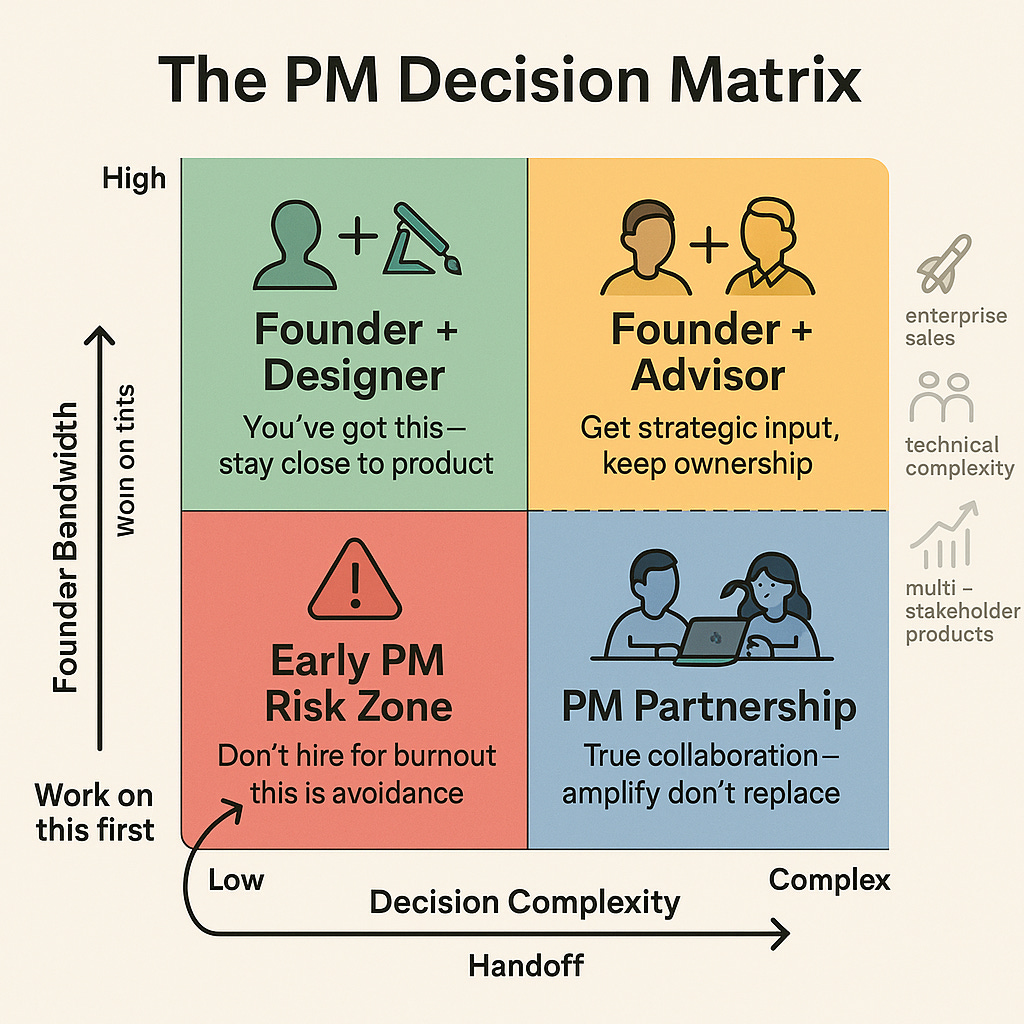

When PMs Do Matter, and How to Know You’re Ready

None of this is to say product managers don’t matter. They absolutely do. Just not always in the way, or at the time, most early-stage startups think.

The truth is, PMs become indispensable after product-market fit, when your product has real users, competing priorities, and multiple teams trying to build, ship, and scale without stepping on each other. That’s when the founder’s brain stops being the bottleneck and starts becoming the liability. It’s not that you’re not smart enough to hold the whole thing anymore, it’s that the whole thing has grown beyond what one person should try to hold. That’s when you bring in a PM not to “own” the product, but to operationalize clarity. To scale your intent. To become the connective tissue between user insight, business priorities, and engineering capacity.

You’ll know you’re at this stage when the following things start to break:

Your team is shipping features with no real coordination across functions.

You’re spending more time re-explaining priorities than setting them.

No one knows what “good” looks like unless you’re in the room to define it.

You’re getting user feedback you should’ve anticipated, but didn’t.

That’s when a PM becomes oxygen. Not before.

And even then, it’s not about throwing in a mid-level hire and hoping for magic. Your first product manager should be someone with enough depth to hold ambiguity alongside you, not someone who just wants to run rituals. They need to be able to push back, to think critically, to build trust with engineering, and most importantly, to align deeply with the vision you’ve already started articulating. They’re not there to figure it out for you. They’re there to help figure it out with you, and to make sure the figuring doesn’t fall apart at scale.

Before you hire your first PM, ask yourself:

Do we have multiple active product streams that need coordination?

Is lack of prioritization slowing us down more than lack of clarity?

Am I truly ready to delegate, not just tasks, but decision-making logic?

Is this person walking into a culture of ownership, or being asked to create one from scratch?

If your answers point to real need, great. Hire a product manager and set them up to succeed.

But if your motivation is more about discomfort than scale, pause.

There’s still more work you need to own.

But What About Structure? The Strongest Case for Early PMs

I'd be doing you a disservice if I didn't steel-man the other side of this argument. There are legitimate reasons why some early-stage startups do benefit from bringing in a PM early, and ignoring them would make this piece less useful.

The coordination problem is real. If you're a technical founder working with two engineers and a designer, someone needs to translate between business logic and technical constraints. If you're spending more time in Slack trying to align everyone than building, a PM can absolutely provide relief. The question is: are you hiring them to solve a coordination problem, or to avoid difficult decisions?

Some founders genuinely can't context-switch. If you're a deep-tech founder who thinks in algorithms, not user journeys, forcing yourself to become product-fluent might slow down the thing you're uniquely good at. A strong PM who can bridge your technical vision with user reality isn't outsourcing, it's specialization.

Market complexity varies. If you're building for enterprise buyers, regulated industries, or multi-sided marketplaces, the stakeholder management alone can justify a PM role. The more variables you're juggling, like different user types, compliance requirements, and integration needs, the more valuable someone becomes who can hold all of that complexity without dropping threads.

Your designer might not want the job. Not every great designer wants to think strategically about roadmaps, talk to enterprise customers, or negotiate scope with engineering. Some want to design, period. Forcing a purely creative person into a product strategy role can backfire spectacularly.

Here's the test: if you can honestly say "I need someone to help me make better decisions" rather than "I need someone else to make these decisions," then you might be ready for a PM earlier than I've suggested.

The key distinction is partnership versus handoff.

An early PM should amplify your product instincts, not replace them.

Putting It All Together: You Don’t Need a PM, You Need to Lead

There’s a seductive myth in startup culture that if you just hire the right person, your hardest problems will dissolve. But the hardest problem at an early-stage company is rarely execution.

It’s clarity.

And clarity doesn’t come from process.

It comes from closeness: closeness to users, to the product, to the why of what you’re building.

That’s not something you can outsource. Not at this stage.

What early-stage startups need most isn’t a product manager.

They need a founder who acts like one.

Not forever. But for long enough to:

Talk to the first hundred users yourself.

Ship the version you’re a little embarrassed of.

Kill your darlings before your customers do.

Feel the pain of what’s broken deeply enough to want to fix it.

Then, and only then, do you start thinking about how to make the machine run smoother. That’s where PMs shine. That’s when it’s worth building process. That’s when your job shifts from discovering the product to scaling its impact.

Until then? Partner with a designer who thrives in chaos. One who’s obsessed with users. One who wants to prototype, test, and throw it away tomorrow if it doesn’t work. Build a tight loop between founder, designer, and tech lead. Make decisions fast. Own the consequences.

And most importantly: stay close.

Stay uncomfortable.

Stay in the mess.

Because the early stage is not a phase you manage your way through.

It’s a phase you design your way out of.

Final actionables, if you're in the thick of this right now:

If you’re about to hire a PM, write down the actual problem you're solving. Is it coordination? Burnout? A clarity gap? Be honest.

Audit your team. Do you have a designer who could step into a more product-strategic role if given the support?

Block time to talk to users yourself this week. Not a report. Not a survey. A call.

Recommit to making one uncomfortable product decision without outsourcing it.

Delay hiring a PM until the questions you’re asking have started to repeat. That’s when you're ready for process.

Your company doesn’t need more roles. It needs more courage.

So before you hire a PM, ask yourself: is this decision about moving forward, or about avoiding discomfort?

If it’s the latter, sit in it just a little longer.

That’s where the real product sense gets built.

You don’t need a buffer. You need a backbone. Be that.