Taste, Instinct, and the Four Ways We Think

A few years ago, I watched a founder kill her own company in slow motion.

She had immaculate taste. Her pitch decks were architectural masterpieces: clean typography, elegant phrasing, references to obscure design theory. Every product mockup was fit for a museum. Every investor update read like a short story. But her decisions? Glacial. Opportunities came and went while she fussed over the kerning in her logo. Her taste was a telescope trained on perfection, but telescopes don’t move on their own.

On the other side of the table, I’ve met founders who are all instinct. They’ll greenlight a pivot before breakfast, rewrite the product roadmap in a single caffeine-fuelled afternoon, and have no idea why half their experiments succeed and half burn cash. Their gut is quick, but it’s also easily misled. They think “movement” equals “momentum.” It doesn’t.

I’ve seen this from both sides of the table (and lived it myself.)

Two years ago, I passed on a founder who is now running a $50M company.

On paper, the decision made sense. Their deck was messy, the brand felt half-baked, and my taste told me it wasn’t ready for prime time. What I didn’t clock, what my instinct was trying to tell me, was the way the founder never lost eye contact when I pushed them on hard numbers. The way they laughed off a competitor’s recent raise and immediately outlined how they’d steal their customers.

I ignored that signal. Taste won. I lost.

We talk about taste and instinct as though they’re two separate tools in the box. In reality, they’re more like two muscles, and the strongest decision-makers know when to flex each.

For years, we’ve been taught to frame this as a simple choice:

Be the thinker, or be the doer.

Have taste, or have instinct.

Kahneman’s System 2 (slow, deliberate) or System 1 (fast, intuitive).

That binary is wrong.

When they measured people's thinking dispositions, not just how they responded in a single moment, but the styles they consistently preferred, they found something that blew up the binary entirely. Four distinct profiles emerged.. Which means the real challenge isn't picking a side, it's knowing when each mode serves you.

Which means the real challenge isn’t picking a side in the taste vs. instinct debate; it’s knowing when to be open, when to be decisive, when to coast on intuition, and when to grind through the cognitive heavy-lifting.

And now, neuroscientists can literally watch your brain flip between these modes. System 1 (instinct) lights up with parietal alpha waves, the hum of well-worn memory pathways firing automatically. System 2 (taste) burns frontal theta, the mental strain of working memory and control.

Your "gut" and your "good judgment" aren't mystical forces floating somewhere in your psyche. They're as physical as your heartbeat, with electrical signatures you can measure. Which means they can be trained. And they can betray you if you lean on the wrong one at the wrong time.

Let me be precise about what I mean by these terms, because they're doing double duty:

Taste has two layers:

Surface level: Cultural sensibility, knowing what your tribe considers "good." This is learned, contextual, and varies by group.

Deep level: The cognitive ability to evaluate, compare, and refine. This is the slow, deliberate mental process of weighing options against standards.

Instinct also has two layers:

Surface level: Gut feeling, the immediate sense that something is right or wrong, often felt in your body before your brain catches up.

Deep level: Fast pattern recognition based on accumulated experience. This is your brain's rapid-fire access to stored knowledge.

The confusion happens because both operate through the same neural pathways. Cultural taste becomes automatic (feels like instinct). Domain expertise becomes instant (looks like intuition).

For the rest of this piece, when I say "taste," I mean the deliberate, evaluative mode, regardless of whether you're applying cultural standards or universal principles. When I say "instinct," I mean the fast, pattern-matching mode, regardless of whether it's based on evolved responses or learned expertise.

The key insight: these aren't opposite forces. They're different gears in the same cognitive transmission.

I’ve spent the last few months thinking about how I can personally break through the binary. About how to cultivate instincts with taste, and taste with instinct. About what happens when you integrate the four thinking styles into your creative and strategic life, and how to know, in the moment, whether you need to telescope out or sprint forward. This is what I know till now.

Because in a world drowning in data but starved of good judgment, the real edge is not thinking faster or thinking slower. It’s thinking in the right way, at the right time, for the right problem.

The Old Binary: Taste vs. Instinct

Before we had EEG readouts and four-part cognitive style models, the conversation was simpler.

We called it good taste versus good instinct. And in almost every creative or strategic field, one of these became the default currency.

Taste was the cultivated kind: the ability to look at a painting, a business plan, a product demo, and know whether it met a certain standard of beauty, clarity, or excellence. It’s reflective and deliberate. It’s shaped by what you’ve been exposed to, what you’ve studied, and what your culture has told you is worth admiring. A person of taste can spot a cliché from across the room. They can tell you why one paragraph sings and another flattens. They know what good feels like.

Instinct is different. It’s the body leaning forward before your brain can explain why. It’s the quick decision in the meeting because something in the founder’s tone just doesn’t add up. It’s the yes you give a deal before you’ve done the math, and the math later confirms you were right. Cognitive scientists call it System 1 thinking: fast, automatic, and often unconscious. It’s rooted in evolutionary survival: notice the danger before you can name it, grab the opportunity before it disappears.

If you’ve ever had sweaty palms in a meeting before realizing the numbers didn’t make sense, that was instinct picking up the signal before taste caught up.

Mini Field Guide: How to Tell Which One You’re Using

Taste feels slow and slightly effortful. You're comparing options, recalling principles, weighing consequences, whether those principles come from design school or ten years of looking at pitch decks.

Instinct feels fast and slightly inevitable. The answer lands before you’ve made a case for it. Your body often reacts first, leaning in, tensing up, feeling a rush.

Check-in question: Am I narrating my reasoning (taste) or am I just moving (instinct)?

Philosophers have been arguing about this split for centuries. Schopenhauer saw taste as a pure, almost sacred detachment from the messy urges of instinct, a way to escape the chaos of life. Nietzsche, predictably, laughed at that. To him, instinct was life itself, but it had to be sharpened and disciplined into what he called a “higher taste.” John Dewey, the pragmatist, put it plainly: reason might point to the door, but instinct gets you to turn the handle.

In practice, neither faculty works well alone.

Taste without instinct becomes the critic’s curse: sharp-eyed, slow-moving, trapped in the perfectionist’s loop of “almost ready.” I’ve seen founders with exquisite taste waste years polishing their brand while someone else, with half the skill but twice the instinct, launched, learned, and overtook them.

Instinct without taste is the hustler’s curse: always in motion, burning cash and goodwill on ideas that feel good but go nowhere. WeWork under Adam Neumann started here: an inspired gut call about “selling community” that eventually collapsed under its own lack of disciplined taste.

The old binary, taste or instinct, thinker or doer, makes for good motivational posters. But it’s a dangerous simplification. It tempts you to over-identify with one mode, and in doing so, to ignore the situations where the other is not just useful but vital.

Which is why the new research matters: the real story isn’t two modes in opposition. It’s multiple dispositions you can shift between, and the rare people who can blend them on demand.

The New Science: Four Thinking Styles

For decades, the story went like this: System 1 (fast) versus System 2 (slow). Instinct versus taste. Gut versus head.

But in 2024, psychologists Christie Newton, Justin Feeney, and Gordon Pennycook decided to look closer, and what they found should make anyone who’s been loyal to one “side” of the binary a little uncomfortable.

When they measured people’s thinking dispositions, not just how they responded in a single moment, but the styles they consistently preferred, they found four distinct profiles:

Actively Open-Minded Thinking: The willingness to seek out, consider, and even integrate perspectives that contradict your own. These people aren’t just analytic; they’re agile. They can update their taste when new evidence demands it.

Close-Minded Thinking: The mental locked door. Decisions feel final, even when they shouldn’t. This isn’t just “bad taste” or “bad instinct”, it’s taste and instinct refusing to collaborate with reality.

Preference for Intuitive Thinking: The fast, fluent, gut-first decision-maker. They trust alpha-wave memory access. They want to feel the answer before they can explain it.

Preference for Effortful Thinking: The cognitive weightlifters. They find satisfaction in wrestling with complexity, even when a simpler answer is staring them in the face.

What’s interesting is that these aren’t momentary switches like “I was in System 1 mode this morning.” They’re dispositions. Your home base. And your home base shapes whether you’ll reach for instinct or taste first, and how likely you are to let the other in.

This is where the taste/instinct framework needs upgrading.

A founder with Actively Open-Minded Thinking can catch themselves before they over-polish (taste over instinct) or over-react (instinct over taste). They move between modes.

A Close-Minded leader might have brilliant instincts or impeccable taste, but either way, they’ll double down on bad calls because the other mode never gets a say.

A Preference for Intuitive Thinking without cultivated taste can turn into charming chaos.

A Preference for Effortful Thinking without trust in instinct can turn into elegant paralysis.

You don't need to become some perfectly balanced cognitive athlete. You just need to know where you naturally land, then build up the muscles you've been neglecting. Because in high-stakes moments, your disposition will decide which tool you reach for, and whether you’ll notice the better tool sitting right beside it.

Inside the Brain: Alpha vs. Theta

If taste and instinct feel abstract, here’s the good news: neuroscientists can now watch them in action.

System 1, the instinctive mode, shows up as a rise in parietal alpha power on EEG scans. Alpha is your brain’s “autopilot hum,” a sign you’re tapping stored patterns in long-term memory without consciously unpacking them. This is what’s firing when a chess master sees a position and just knows the right move, or when a firefighter senses the floor is about to collapse before the first crack appears.

System 2, the reflective mode we associate with taste, shows a spike in frontal theta power. Theta is your brain’s signal for cognitive control and working memory. It’s what happens when you’re deliberately holding multiple ideas in your head, weighing trade-offs, and resisting the pull of the easiest answer.

If alpha is a jazz musician’s fingers moving before they can name the chord, theta is the moment they pause mid-performance, re-anchor to the key, and adjust to keep the harmony intact.

The shift between these two isn’t just theory, it’s physical. Your brain’s electrical rhythms are literally changing. And here’s the important part: you can train them.

More exposure and feedback in a specific domain strengthens the alpha-driven instinct, making those gut calls faster and more accurate.

Deliberate practice in structured problem-solving deepens theta control, so your taste can intervene when instinct wants to sprint off a cliff.

This is why both the veteran venture capitalist and the master chef can “trust their gut”, but only in their field. Their alpha rhythms are pulling from a vast, domain-specific archive of patterns. Put them in each other’s kitchens or cap tables, and their instincts won’t be worth much. Without the taste built from years of theta-driven refinement, the gut becomes just another guess.

In other words: your brain already knows how to dance between taste and instinct. The question is whether you’re giving it enough training, in the right contexts, to make that dance worth watching.

Domain-Specificity: Why Your Gut Is Not Universal

One of the most persistent myths in business, art, and leadership is that a “good gut” is portable. That if you’re decisive in a boardroom, you’ll be decisive in a kitchen; if you can sniff out a great investment, you can sniff out a great painting.

You can’t.

True expert intuition, the kind that’s as fast as it is accurate, only emerges after about 10 years of deep, focused exposure in a single domain. Chess masters can hold around 50,000 board patterns in memory. ER doctors, firefighters, and elite athletes make more than 80% of their calls through unconscious pattern recognition. But the key word is patterns. Those patterns are learned, hard-won, and specific.

Take a venture investor who’s been making early-stage SaaS bets for a decade. Their gut is a machine in that space: they can pick up on founder body language, roadmap pacing, market signals before the pitch deck is done. Drop them into climate tech or consumer packaged goods, and that “gut” suddenly looks a lot more like guesswork. Their alpha rhythms are still humming, but they’re pulling from the wrong archive.

The same is true in creative fields. A Michelin-star chef can improvise a perfect tasting menu because their brain has catalogued thousands of flavor combinations. Ask them to compose a jazz piece, and their instinct is no better than yours.

Recognising True Instinct vs. Impulse

Before you act on a gut call, run it through this filter:

Pattern familiarity: Does it feel right because you’ve seen this before, or because it’s excitingly new? True instinct comes from recognition, not novelty.

Body signals: Did your body react before your brain did? Micro-tension, a sudden ease, a subtle jolt?

Low cognitive load: Did the answer appear without mental strain? If you had to grind for it, you’re in taste mode, not instinct mode.

Verification habit: Do you have a record of past gut calls in this domain, and do they hold up? A simple gut-call journal can separate skill from bias over time.

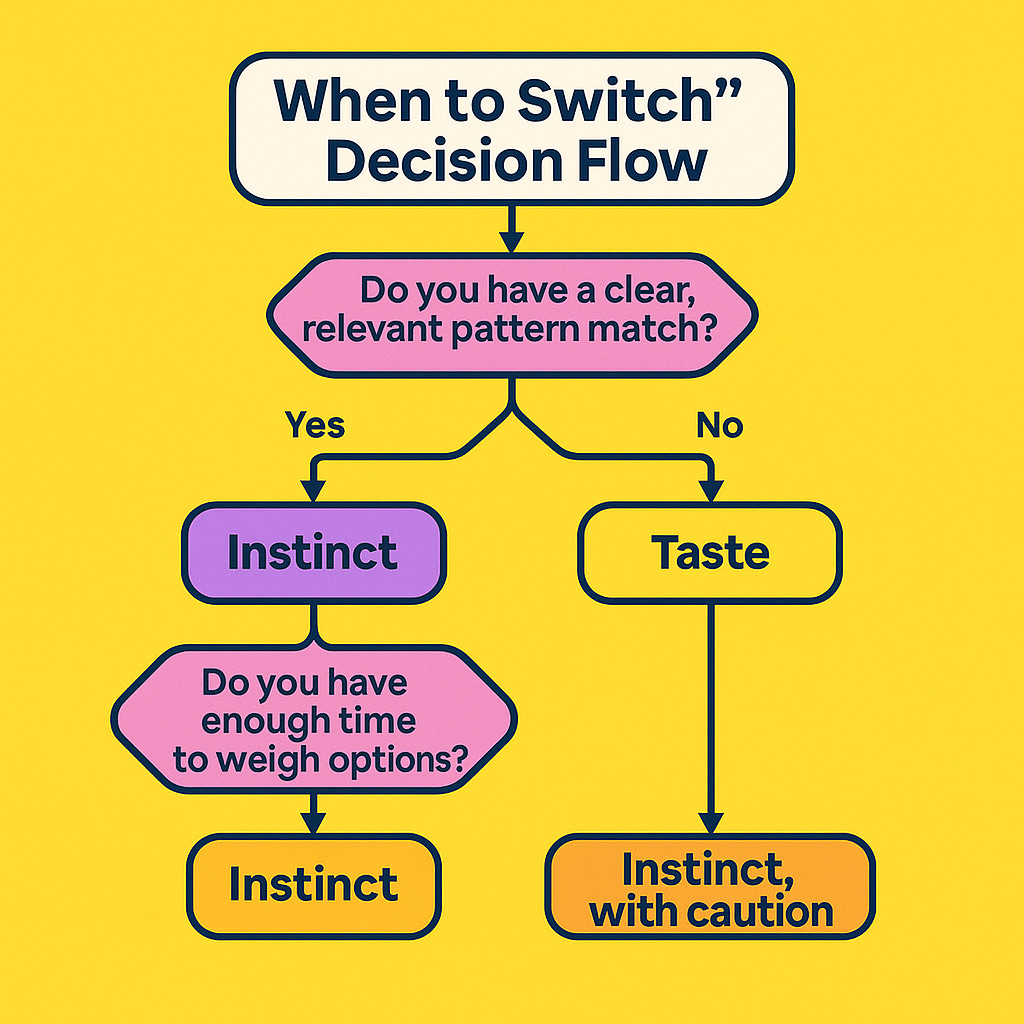

This is where taste and instinct need each other most. Taste, the slow, reflective mode, is what helps you recognise when you’re out of your lane, when your gut might be operating on incomplete or irrelevant patterns. And instinct, once trained in a domain, is what lets you actually move when the clock is ticking and the data is incomplete.

The trap is assuming that because your instinct works somewhere, it works everywhere. That’s how you get the overconfident founder who tries to blitzscale every idea, or the investor who throws money at a hot space they’ve never touched before.

Domain-specificity isn’t a weakness; it’s a reality. The goal isn’t to make your gut universal, it’s to make it accurate where it counts, and to have the taste to know where it doesn’t.

Culture & Universals

If taste were purely cultural, we could explain every preference by pointing to where and how you grew up. If it were purely instinctual, we’d all agree on what’s beautiful, moving, or worth keeping.

Reality, as usual, sits in the messy middle.

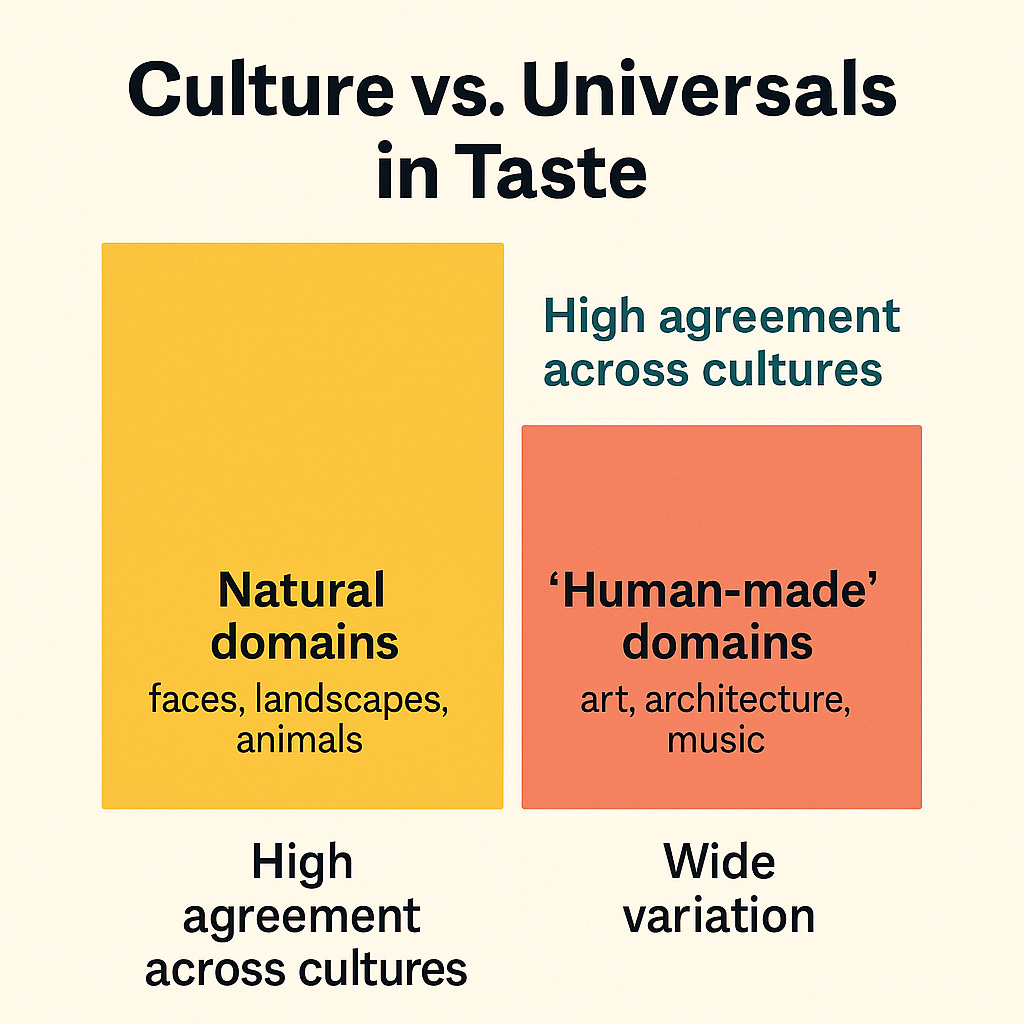

Large-scale cross-cultural research from 2024–2025 found something surprising: our agreement on beauty depends on the domain. When the subject is natural (faces, landscapes, animals), the overlap is huge. Across continents and cultures, people tend to agree on which landscapes are calming, which faces are attractive, which animals look “majestic.” But when the subject is human-made (paintings, buildings, music), agreement splinters. Here, taste fragments into local dialects, shaped by what your culture celebrates and what it teaches you to ignore.

This changes everything about how we think about taste and instinct: part of what we call “taste” may actually be instinct in disguise: an evolved, near-universal preference for certain natural forms. And part of what we call “instinct” may be nothing more than deeply internalised cultural taste, so ingrained it feels automatic. This is why the taste/instinct distinction isn't about cultural vs. natural, it's about slow vs. fast processing, regardless of where your standards come from

The other twist: self-reference. New research shows that aesthetic judgment isn’t just about form or function; it’s about personal relevance. We rate something as beautiful faster and higher if it feels like it belongs to us in some way. If it resonates with our memories, our values, our story. Your “gut” reaction to a song might be less about the chord progression and more about the summer you first heard it.

Here's the practical takeaway: when you're building something for mass appeal (a consumer product, a viral campaign, a universal story), lean into the patterns that tap our shared instincts. Clean lines, natural proportions, faces that look trustworthy. But when you're targeting a specific tribe (luxury buyers, crypto natives, indie film lovers), that's where cultural taste becomes your secret weapon. The more niche your audience, the more their learned preferences will override their evolutionary ones. A Patek Philippe watch doesn't succeed because it looks "naturally beautiful"; it succeeds because it signals membership in a very particular taste culture.

Which means that even the most trained taste has a private gravity. And even the most universal instinct passes through the filter of your own history before it lands.

For a creator, strategist, or investor, this matters because it complicates the feedback loop. When you feel a strong reaction, whether it’s alpha-wave instinct or theta-driven analysis, you have to ask:

Is this grounded in a universal pattern most people will share?

Or is this anchored in a cultural or personal lens that won’t travel well?

The most interesting work, I think, happens when you can toggle between both: trusting the part of your taste that is humanly universal, while also wielding the part that is gloriously, specifically yours.

How to Train Both

The good news is that neither taste nor instinct is fixed. Your brain is not a static operating system; it’s a rewritable codebase. Neuroplasticity research in the last few years has shown that the networks supporting both intuitive and analytic thinking can be strengthened with deliberate practice, not just in childhood, but throughout adulthood.

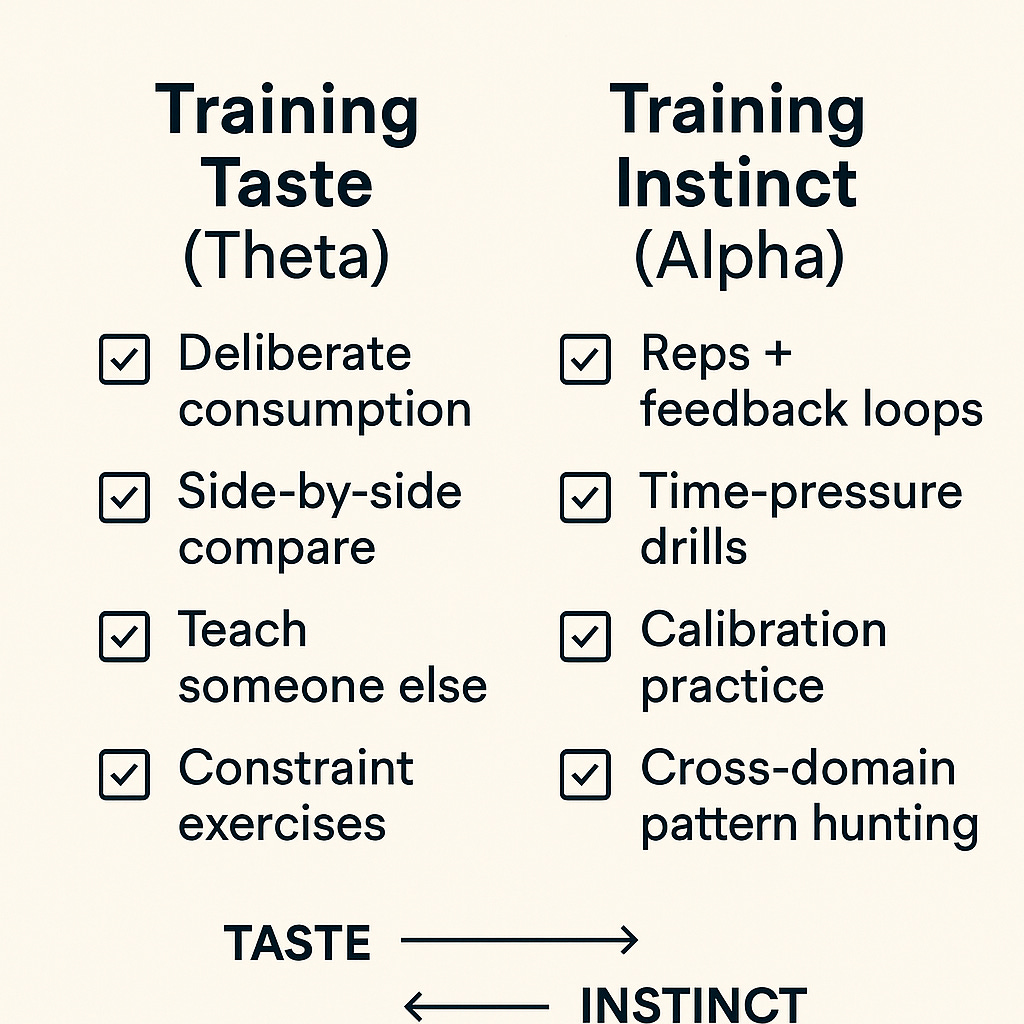

But here’s the catch: you don’t train them in the same way.

Training Taste (Theta Mode)

Taste lives in the slow, deliberate networks, the frontal theta rhythms of working memory, cognitive control, and careful discrimination. To sharpen it, you need to feed it high-quality input and force it to make distinctions.

Six ways to deliberately build taste:

Deliberate Consumption: Immerse yourself in the best examples in your domain, but never passively. Ask: Why is this better than the rest? Break it apart until you can name the differences.

Compare Side-by-Side: Force your brain to notice fine distinctions between similar but unequal options. Two logos, two proposals, two menu layouts. Choose a winner, then justify it.

Teach Someone Else: Nothing sharpens taste like having to articulate why something works. Find a junior colleague or friend and explain your aesthetic choices. If you can't make them see it, you don't really see it either.

Constraint Exercises: Give yourself artificial limits to force finer discrimination. Pick your five favorite restaurants and rank them. Then pick your top two and explain why one beats the other. Constraints force your taste to get specific.

Cross the Borders: Learn from fields outside your own to avoid narrow, inbred taste. An architect studies dance. A filmmaker studies Japanese carpentry. A founder studies haute couture. This is how taste evolves.

Slow One Decision Per Week: Once a week, take a decision you'd normally make fast and over-analyse it. This builds your "Preference for Effortful Thinking" muscle from the four-styles model.

Document your taste decisions over time. You’ll start to see recurring principles that are uniquely yours, your personal standard of excellence.

Training Instinct (Alpha Mode)

Instinct lives in the parietal alpha networks: fast, automatic pattern recognition built on experience. To strengthen it, you need to do the reps and get immediate feedback.

Six ways to turn instinct into a superpower:

Reps + Feedback Loops: Decide quickly, see the result, adjust. The shorter the feedback loop, the faster your instinct improves.

Calibration Practice: Start making predictions with confidence levels. "I'm 70% sure this hire will work out." "I'm 90% sure this feature will flop." Track your accuracy over time. This teaches your gut to distinguish between strong and weak signals.

Time-Pressure Drills: Force yourself to make calls with incomplete data under tight deadlines, then review them later in slow mode.

Cross-Domain Pattern Hunting: Practice spotting structural similarities between different fields. How is a startup pitch like a jazz performance? How is market timing like surfing? This expands your pattern library.

Domain Saturation: Immerse yourself in the specific context you want instincts for. Watch hundreds of pitches if you're a VC. Plate hundreds of dishes if you're a chef. Instincts don't generalise well.

Recover Fast: Treat wrong gut calls as data, not embarrassment. Do post-mortems. Instinct improves by failing small and often.

Keep a “gut-call journal” for one month. Write down what your instinct told you, why you think it said that, and what actually happened. The patterns (and the blind spots) will become obvious.

When you train both, you’re not just getting better at each mode, you’re building the ability to switch between them fluidly. That switch is where mastery lives.

Creativity’s Golden Ratio

When we picture creativity, we tend to imagine one of two extremes. The freewheeling genius, pouring ideas onto the page in a blur of inspiration. Or the meticulous craftsman, hunched over the workbench, perfecting the details until they gleam.

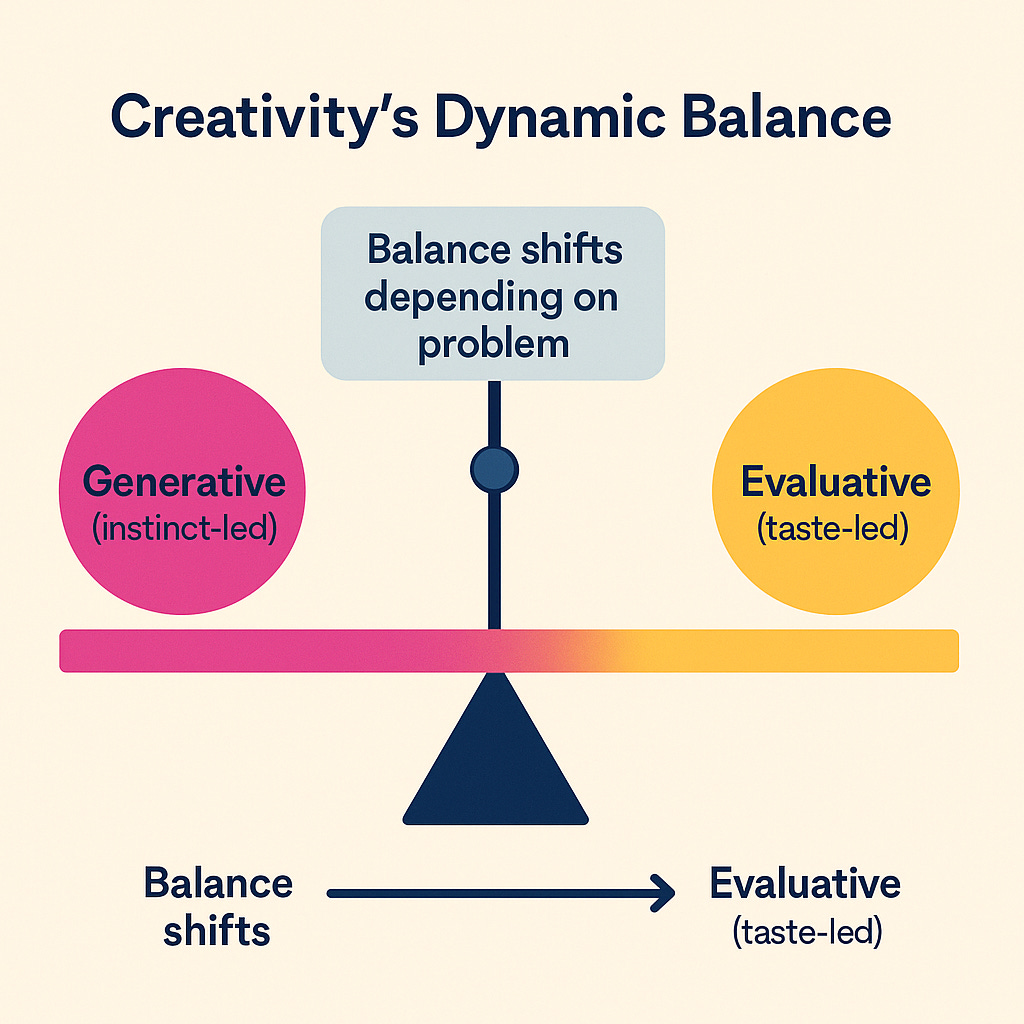

Recent research on creative cognition shows that most breakthroughs come from alternating between two modes:

Generative: loose, intuitive, instinct-led, happy to make a mess.

Evaluative: tight, deliberate, taste-led, intent on sorting the signal from the noise.

In jazz improvisation, this means riffing fearlessly for eight bars, then pulling back into the melody before the audience drifts. In product design, it means sketching ten wild prototypes without judgment, then spending the afternoon deciding which one actually solves the problem.

Some researchers talk about a “golden ratio” in creativity- not a fixed number, but a dynamic balance between generative (instinct-led) and evaluative (taste-led) phases. The balance shifts with the problem: ambiguous challenges need more instinct; constrained ones need more taste.

But here's what the research doesn't tell you: how to recognize which mode the moment demands. Some problems scream for instinct: a crisis unfolding, an opportunity that won't wait, a creative block that needs breaking. Others demand taste: a final design review, a make-or-break pitch, a strategy that has to work the first time. The real skill is learning to read the moment, both what's happening around you and what's happening inside your own head. When you feel paralyzed by options, that's instinct calling. When you feel rushed toward a mediocre solution, that's taste tapping its foot.

If you’ve ever heard Ira Glass talk about “the taste gap”, that painful early stage where your taste is good but your output isn’t, this is the escape route. You can’t close the gap by sitting still in evaluative mode, waiting for your skills to catch up. You close it by doing a lot, letting instinct spill onto the canvas, and then pulling taste into shape the mess.

This is why so many creative careers stall:

The taste-first people smother ideas before they’ve had a chance to grow.

The instinct-first people never stop long enough to see what’s actually working.

The professionals in art, business, and science aren’t necessarily more gifted. They’re just better at oscillation. They know when to take their foot off the brake and when to slam it down. They know that the early mess is supposed to look ugly, and that refinement is supposed to be uncomfortable. They trust both phases because they’ve built muscle memory in switching between them.

And here’s the kicker: this isn’t just “creative advice.” It’s the same skill set great strategists, negotiators, and leaders use when they bounce between instinct and taste in real time. It’s the pivot in a sales pitch, the mid-game change in a football match, the gut call to abandon a plan, followed by the cool-headed analysis to make the new one work.

The art is in knowing which mode the moment calls for. The craft is in training, so they’re equally ready to answer.

The Social Dimension: When Taste and Instinct Collide

None of this happens in isolation. Your taste and instinct are constantly bumping up against other people's, and that's where things get interesting and complicated.

I've seen founding teams implode because the CEO was all instinct ("Let's pivot now!") and the CTO was all taste ("But we haven't tested this properly"). I've watched design reviews turn into blood sport because the creative director's taste felt like a personal attack on the engineer's instincts.

The highest-performing teams I know have learned to choreograph this dance. They have rituals:

Instinct rounds: Everyone gives their gut reaction before anyone explains their reasoning. No justification is allowed for the first five minutes.

Taste audits: Dedicated time to step back and ask whether the fast decisions are adding up to something coherent.

Mode calling: Someone has permission to say "We're stuck in analysis" or "We're moving too fast" and shift the room's cognitive gear.

The trap is assuming everyone's operating in the same mode. When your instinct is screaming "yes" and your co-founder's taste is whispering "wait," that's not necessarily a disagreement about the decision. It might be a disagreement about which mode the moment calls for.

The best leaders I know are bilingual: they can speak both instinct and taste, and they can translate between them for their teams.

When Both Modes Fail

Before we wrap with the success stories, let's talk about the failure modes. Because both taste and instinct can be hijacked, and when they are, they'll confidently lead you off a cliff.

Taste can be corrupted by:

Status anxiety: Choosing what looks impressive rather than what works

Analysis addiction: Using research as procrastination in disguise

Perfect-world fallacy: Optimizing for ideal conditions that don't exist

Instinct can be corrupted by:

Ego protection: "Trusting your gut" when your gut is just avoiding uncomfortable truths

Recency bias: Your pattern recognition pulling from the last thing that happened, not the most relevant thing

Stress cascade: Fight-or-flight mode masquerading as decisive leadership

The warning signs are physical. Corrupted taste feels tense and grinding. You're working hard but nothing's getting clearer. Corrupted instinct feels manic and brittle. You're moving fast but can't explain why to anyone, including yourself.

The antidote is usually switching modes entirely. When taste is spinning its wheels, force an instinct break: make any decision, see what happens. When instinct is running hot, force a taste pause: explain your reasoning to someone who wasn't in the room.

In Closing

We started with the old binary: taste or instinct. Thinker or doer. We’ve moved through the new science four thinking styles, alpha and theta rhythms, domain specificity, cultural universals, and creativity’s golden ratio.

And now we’re back to the core truth: neither mode is enough on its own.

Taste without instinct is analysis paralysis, knowing what’s good but never making it. Instinct without taste is motion without progress, doing everything, but not the right things.

The real edge in art, business, strategy, or life comes from integration.

From being able to switch between:

The open-minded explorer who invites new inputs,

The grounded analyst who applies standards,

The intuitive mover who acts without overthinking,

The disciplined builder who stays in the hard, effortful work long enough to make it real.

That’s not a personality trait. That’s trained agility. And the people who have it are the ones you remember: the leader who can call the bold shot in a crisis, then quietly pore over the details in the aftermath; the artist who can explode the canvas with energy and then trim it to perfect balance.

Your 7-Day Experiment

Pick one of these three tracks for a week, or run them sequentially over three weeks for deeper practice.

Track 1: Mode Switching

Identify your home base. Then, daily, do one small task in your opposite mode.

Track 2: Meta-Skill Practice

Before big decisions, ask: “Does this need instinct or taste?” Try calling your mode out loud in group settings.

Track 3: Failure Mode Detection

Track when your mode feels hijacked (by stress, ego, time pressure) and practice the antidote.

Track 1: Mode Switching

Identify your home base. Are you more taste-first or instinct-first? More open-minded or close-minded? More intuitive or effortful?

Pick your opposite. For one week, design one small daily task that forces you into the other mode.

Taste-first? Make five fast decisions before lunch, no overthinking.

Instinct-first? Spend an hour analysing one problem without acting on it.

Track 2: Meta-Skill Practice

3. Read the room. Before making any significant decision this week, pause and ask: "Does this moment need instinct or taste?" Notice when you get it wrong.

4. Call your mode. When working with others, try saying out loud: "I'm in taste mode right now" or "My instinct says..." See how it changes the conversation.

Track 3: Failure Mode Detection

5. Track the corruption. Notice when your taste feels grinding or your instinct feels manic. What triggered it? Stress? Ego? Time pressure?

6. Practice the antidote. When you catch yourself in a corrupted mode, deliberately switch. Taste spinning? Make any decision. Instinct running hot? Explain your reasoning.

7. Review patterns. At the end of the week, ask: where did mode-switching improve your outcome? Where did calling your mode change team dynamics? Where did catching corruption save you from a bad decision?

Taste tells you what's worth doing. Instinct gets you to do it. Everything else is just noise.

What a fantastic read. You opened my mind and gave structure to the random acts I was doing.

I have a doubt, if we define taste and intuition based on the time I've taken during that work, do other things like overthinking, procrastination etc come into play? In what way or to what extent do you see these being relevant factors?

For example, if I have a gut feeling about something, but I'm overthinking unrealistic scenarios because of which I've not used my instinct. Or not recognised it as instinct.