Interesting, Interested

On Attention, Performance, and the Unpostable Life.

I’ve been performing for years.

Not lying, to be clear. Everything I’ve shared has been true. The books, the ideas, the strange connections I draw between things that don’t obviously belong together. All real. But also selected. Arranged. The version of me most likely to make you lean in.

You might subscribe to my weekly reading list. Every Saturday, I bundle together the most interesting things I encountered that week, write little annotations, draw threads between them. People tell me it makes them feel smarter. They screenshot my takes and send them to friends. I love that. I’m not going to pretend I don’t. There’s a specific pleasure in being someone’s source- the friend who always knows about the thing before it becomes a thing, the one who reads the weird stuff so you don’t have to. I built that on purpose. It wasn’t an accident.

Recently I was reading something genuinely strange and wonderful, and I don’t even remember what, which is part of the point, and my first thought wasn’t wow. It was how do I describe this in a way that makes me sound like the kind of person who finds things like this?

I wasn’t reading anymore. I was scouting. The book had become raw material for a future performance of having read it.

This happens more than I’d like to admit. I watch a film, and somewhere around the forty-minute mark, I start composing the tweet. I have a genuine emotion and immediately begin translating it into something shareable, something that will resonate, something that earns its place in the feed.

Susan Sontag saw this coming decades ago, writing about photography. The camera doesn’t just record experience, she argued. It changes the nature of experience itself. You start seeing photographically. The tourist isn’t really looking at the cathedral; she’s looking at the picture of herself looking at the cathedral. The frame precedes the seeing.

I don’t carry a camera everywhere. I carry something worse, an internalised audience. The frame is always up. The seeing is never just seeing.

The experience had become secondary to the narration of the experience. I was auditioning for my own life. And I was so very good at it.

The Economics of Interesting

I didn’t become this way by accident. Being interesting takes a lot of work, and it also works.

It opens doors that stay closed for people who are merely competent. It gets you into rooms where decisions are made, onto lists you didn’t apply for, into DMs from people you admire. The interesting person gets the speaking invitation, the podcast interview, the “you should meet my friend” introduction that changes everything. I’ve watched it happen. I’ve been the beneficiary.

The internet has made this an explicit requirement. Before, you could be privately fascinating- the dinner party guest everyone wanted seated next to them, the colleague who made meetings bearable. Now, fascination is scalable. You can be, sometimes have to be, interesting to thousands of people who’ve never met you. And that interestingness compounds. Followers attract followers. The screenshot gets shared. The algorithm notices you’ve been noticed and notices you more.

There is a well-worn term for this- personal brand. I remember when it first entered the lexicon, around 2008 or so, and how embarrassing it sounded. Your brand? Like you’re a soft drink? A sneaker? The language felt borrowed from a world that had nothing to do with actual personhood.

By 2015, personal brand was startup advice. By 2020, it was career necessity. The cringe faded, or we just got used to it, and the language of marketing colonised the self so gradually that we stopped noticing we’d been occupied. Now, everyone has a brand whether they cultivate one or not. The only choice is whether you manage it deliberately or let it be managed by accident.

I understood this early. Not consciously, but in the manner you understand any economy you’re trying to survive in. I understood that my ideas were currency, that my references were signals, that the way I synthesised disparate things into unexpected wholes was a kind of value I could trade on. So I got better at it. I learned which observations resonated, and which ones didn’t. I developed a sense for the interesting-shaped hole in any conversation and became adept at filling it.

Guy Debord called it the society of the spectacle. He was writing in 1967, long before any of this existed, and yet he saw it clearly: “Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.” He was talking about mass media, about advertising, about the way images mediate our relationship to reality. But he was also describing something more intimate, the way we become spectacles to ourselves. The merger of being and appearing. The inability to experience something without simultaneously representing it.

This isn’t a confession of some shameful inauthenticity. I genuinely am curious. I genuinely do read widely and think in connections and care about ideas. The performance wasn’t a lie, but it was an optimisation. I was taking the most interesting parts of myself and turning up the volume, letting the rest fade into background noise. The girl who watches reality TV and cries at dog videos and sometimes goes weeks without a single original thought, she was still there, but she wasn’t the product.

And the product was good. I won’t pretend otherwise. The interesting version of me built a career, an audience, a reputation. She got me out of rooms I wanted to leave, and into rooms I wanted to enter. I’m not ungrateful. I’m just tired.

The Cost You And I Pay

The tiredness is hard to explain because it doesn’t look like anything from the outside. It’s not burnout in the way people usually mean. I’m not exhausted from overwork or crushed by deadlines. I sleep fine. I meet my commitments. From the outside, I look like someone who has it figured out.

Byung-Chul Han calls it the burnout society. The exhaustion isn’t coming from external demands, from a boss or a system pressing down on you. It’s coming from inside. We have become, he says, “entrepreneurs of ourselves,” and the entrepreneur never rests because the business is never done. The project of self-optimisation has no endpoint. You can always be more productive, more visible, more interesting. The tiredness I feel isn’t laziness or weakness. It’s the logical destination of turning yourself into a project that can never be completed.

When you’ve optimised for interesting long enough, every experience starts to arrive pre-formatted. I’ll be walking through a market or sitting in a waiting room or overhearing a conversation and I can feel the processing begin. How would I describe this? What does this connect to? Where does this fit in the larger tapestry of things I’ve been thinking about? The moment hasn’t finished happening and I’m already packaging it for later.

I went to NAAR for the new year. Beautiful, delicious, disorienting, everything I wanted. And I remember standingin the washroom, struggling to take in the (insane) view from the washroom, genuinely moved by something I couldn’t name, and within seconds I was composing the caption. Not even for Instagram specifically, just for the generalised audience that now lives in my head. The one that’s always watching. The one I perform for even when I’m alone.

That audience that used to feel like company. That now feels like surveillance.

The research on this is still emerging, but what exists is grim. Studies on self-presentation and social media find a consistent pattern: the more we curate, the more exhausted we become, but the exhaustion doesn’t stop the curating. It’s not a behaviour we can simply decide to quit. The performance becomes structural. We don’t know how to experience things without the frame anymore. One study found that people who took photos of experiences remembered the visual details better but the experience itself worse. The camera ate the moment. The documentation displaced the living.

There’s a loneliness to being known for your taste. People approach you with a certain expectation. They want the version of you that’s always finding things, always synthesising, always a little ahead of the curve. And you deliver, because that’s the transaction, that’s what you’ve promised. But the delivery requires constant vigilance. You can never quite relax into not knowing, not having a take, not being the one with the interesting observation. The role doesn’t have an off switch.

I’ve started to notice what I edit out. The ordinary pleasures that don’t fit the brand. The books I read that are simply fine. The days where nothing interesting happens, where I’m just a person moving through hours without insight. Those parts of life have started to feel like failures. The gaps in the content calendar, missed opportunities to be fascinating. I’ll catch myself feeling guilty about a weekend where I didn’t encounter anything worth sharing. As if living without producing evidence of living is somehow a waste.

The other cost is subtler and I’m only starting to understand it. When you perform curiosity long enough, you stop being able to tell the difference between genuine interest and the performance of interest. I’ll pick up a book and I genuinely can’t tell if I want to read it or if I want to be the kind of person who’s read it. Both feel identical from the inside. The wanting has collapsed into the wanting to be seen wanting.

This is what Debord meant when he said the spectacle isn’t just something we watch, it’s something we become. The image doesn’t just represent life; it starts to substitute for it. And once the substitution is complete, you can’t find your way back to the original. You don’t even remember there was an original.

The Difference

Interesting is something that happens in other people. You can’t feel your own interestingness, you can only infer it from reactions, from the lean-in, from the screenshot, from the “you should write about that.” It’s a quality that exists entirely in the space between you and an audience. Remove the audience and the interesting disappears. The category simply stops applying.

Interested is different. Interested is something you actually experience. It’s the absorption, the forgetting of time, the thing that happens when you look up from a book and two hours have passed and you haven’t once thought about how you’ll describe it later. Interested doesn’t need a witness. It completes itself.

Simone Weil wrote about attention as the rarest and purest form of generosity. But she meant something very specific. Not the kind of attention that takes notes, that processes, that asks “what can I do with this?” She meant attention that empties the self. Receptivity so complete that you disappear into the looking. The object of attention fills the entire frame because there’s no part of you leftover to be observing yourself observing.

I read that years ago and thought I understood it. I didn’t. I thought attention meant the thing I was already doing: reading carefully, noticing patterns, making connections. But that’s not what Weil was describing. She was describing a kind of attention that doesn’t produce anything. That doesn’t have an output. That isn’t, in any sense, generative. You don’t come away with material. You come away changed, or you come away with nothing, and both are fine.

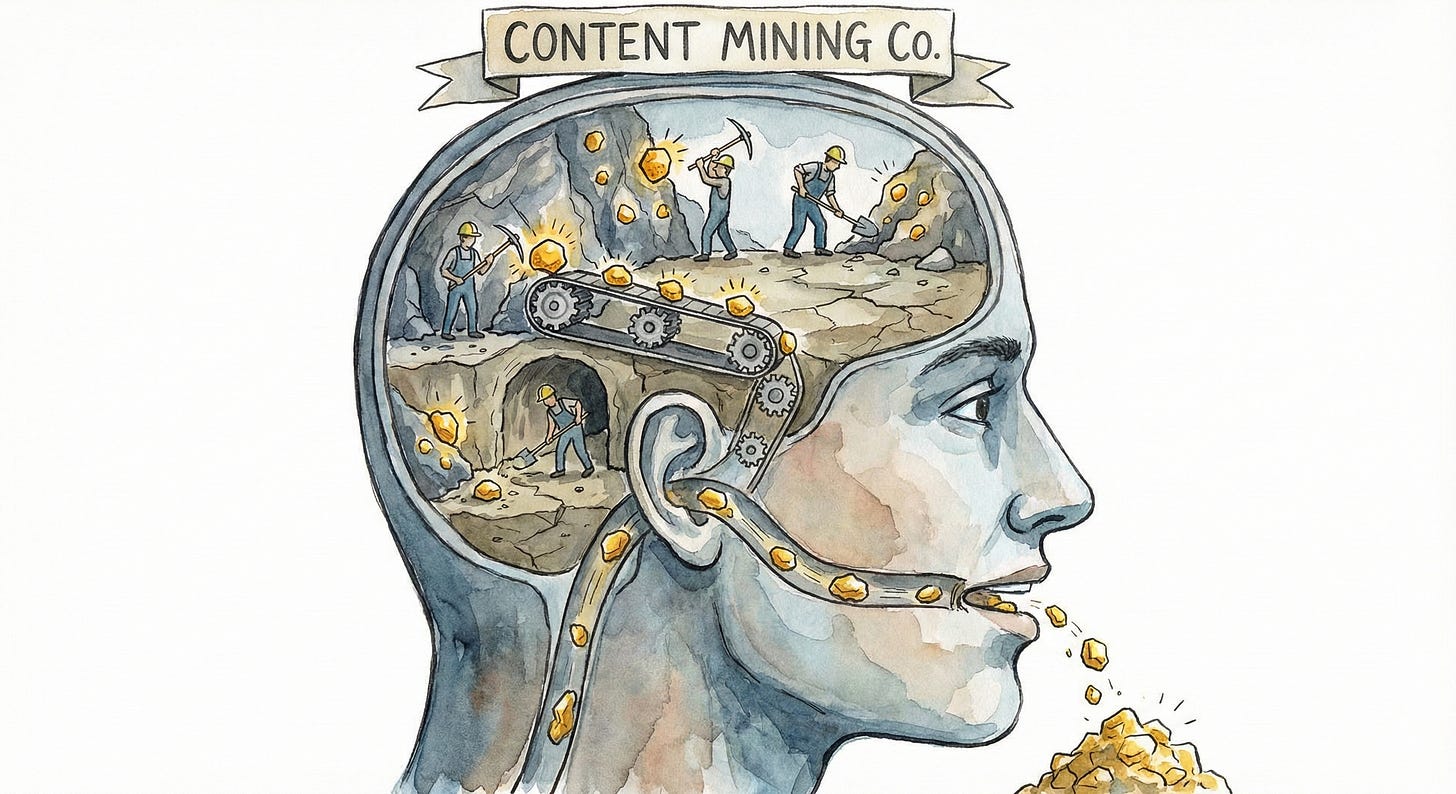

I’ve been confusing these for years. I thought my job was to be interested in things and then share that interest with others. A clean pipeline of input, processing, output. But somewhere along the way, the output started to shape the input. I began selecting what to be interested in based on what would be interesting to share. The curiosity became a sense of usefulness. It was still real, but it was also optimised, which meant it was no longer entirely mine.

This sounds like a humble brag, I know. Poor me, I’m too interesting, people pay too much attention to my carefully curated thoughts. But that’s not quite what I’m trying to say. What I’m trying to say is that I built a machine for generating interestingness and then the machine started running me. The part of me that used to wander, genuinely wander, without destination or purpose, got recruited into the project of being someone worth paying attention to. And wandering with a purpose isn’t really wandering at all.

I think about the difference between a window and a mirror. Interesting is a mirror. You’re always seeing yourself reflected in the other person’s reaction, adjusting, calibrating. Interested is a window. You’re looking out at something that has nothing to do with you. The self recedes. You’re just there, in the presence of the thing, not thinking about how you look in relation to it.

The novelist and essayist Siri Hustvedt put it this way: “To be truly interested in something, you have to be willing to be bored by it.” She meant that real attention includes the dull parts, the longueurs, the stretches where nothing is happening. It means staying with something past the point where it’s yielding content. Most of what I read, I abandon the moment it stops being useful. The moment I’ve extracted what I need. That’s not interest. That’s mining.

I miss being a window. I’m not sure I remember how.

The Unpostable Life

There are things I love that I’ve never told you about.

I love watching amateur cooking videos on YouTube, the badly shot ones where someone’s auntie is making dal in a pressure cooker older than me while yelling instructions at a camera she clearly doesn’t trust. I’ve seen hundreds of these. They have never once made it into a reading list.

I reread the same three comfort novels every year. They’re not particularly good. They’re not even particularly interesting. They’re just mine in a way that doesn’t need to be explained or defended or positioned as a quirky contrast to my otherwise highbrow taste. I’ve never mentioned them because they don’t fit the curation. They’re just ordinary pleasure, and ordinary pleasure doesn’t have a hook.

I like sitting in my car after I’ve parked, sometimes for twenty minutes, listening to the end of a song or a podcast or sometimes nothing at all. Just sitting. No thoughts worth capturing. No insights emerging. Just a person in a stationary vehicle, delaying the transition back into someone who has things to do.

I cry at those videos where soldiers come home and surprise their dogs. Every single time. I find them on purpose sometimes, when I need to feel something that isn’t complicated. This is arguably embarrassing. It doesn’t signal anything interesting about my interior life. It’s just a naked sentimentality that I’ve never figured out how to frame.

These are the parts that don’t make the cut. Not because they’re shameful but because they’re ordinary, and ordinary has no currency in the economy I’ve been trading in. The interesting person has interesting tastes, interesting hobbies, interesting ways of relaxing. She doesn’t just sit in her car. She doesn’t watch aunties make dal. She doesn’t cry at dog videos like everyone else on the internet. Or if she does, she makes it a thing. She writes about it, ironises it, finds the angle that makes it interesting again.

I’m tired of finding the angle.

Researchers have documented how authenticity itself became a genre- the messy bun, the “no makeup” makeup, the casually tossed-off caption that took forty-five minutes to write. We got so good at performing genuineness that the performance became invisible even to us. The “authentic self” we present is still a presentation. It’s just a presentation that’s learned to hide its seams.

I think about Elena Ferrante sometimes. The novelist who refuses to appear. No author photos, no interviews, no readings, no public self at all. Just the books. She called publicity “a garbage disposal” and refused to let her personhood become part of the product. Critics have called it a gimmick, a marketing strategy, but I don’t think that’s right. I think she understood something the rest of us are only starting to grasp: that the author becoming interesting is a threat to the work staying interesting. That the public self cannibalises the private one. That some things can only survive by staying hidden.

I’m not Ferrante. I don’t have that discipline, and I definitely don’t have that faith that the work can stand alone, that I don’t need to be there selling it with my presence, my takes, my carefully curated interestingness. But I understand the impulse now in a way I didn’t before. The appeal of being nobody. The freedom of the unpostable life.

There’s a version of me that exists only in private. The one who doesn’t know things, who hasn’t read the important book, who has no take on the current discourse because she didn’t even notice there was a discourse. The one who sometimes goes entire weeks without a single thought worth sharing. She’s not performing anything. She’s not even really paying attention. She’s just there, existing, unburdened by the need to be witnessed.

I like her. I don’t let her out much.

Zadie Smith wrote about quitting social media, and what struck me wasn’t the quitting itself but how she framed it. Not as a moral stance, not as a rejection of the platform’s politics or ethics, but simply as self-knowledge. “I’m the wrong personality type,” she said. Some people can hold the tension between public and private, can stay present while being watched. Others can’t. Knowing which one you are isn’t failure.

I’m still figuring out which one I am. Maybe I’m neither. Maybe I’m someone who can stay public but needs to protect certain rooms. Needs to keep some doors closed. Needs to let some pleasures stay ordinary, unframed, unshared.

The dal videos. The same three novels. The dog coming home to the soldier. The car after it’s parked. Mine.

The Harder Question

So what am I actually saying here? I’m not quitting the internet. I’m not abandoning the reading list or deleting my accounts or retreating into some performative silence that would itself be a kind of performance. I’m still going to have takes. I’m still going to share them. The machine I built isn’t one I’m ready to dismantle, and I’m not sure I’d want to even if I could.

But then what is this? What changes?

Part of me wonders if it’s even possible to stay public and stay present at the same time. The audience changes things. It has to. The moment you know someone is watching, you become someone who is being watched, and that someone is never quite the same as the one who exists unobserved. Maybe the corruption is built in. Maybe the best I can hope for is to be aware of it, to hold it lightly, to not mistake the performance for the whole.

But that feels like a cop-out.

I’ve noticed something about the burnout confessional as a genre. It has become, itself, content. The “I’m stepping back” post. The “I’ve been doing some thinking” essay. The performed exhaustion, the carefully crafted admission of struggling, all of it feeding the same machine it claims to critique. Even vulnerability has been optimised. Even this essay risks becoming that- another piece of interesting content about the exhaustion of producing interesting content. The snake eating its tail, but plating it for Instagram before it does.

I keep thinking about writers I admire, the ones who seem to produce from some deep interior place, who write like no one is watching even though thousands of people are. I used to think they were simply more talented, more authentic, more immune to the pressures that shape the rest of us. Now I think maybe they just got better at protecting something. Some chamber of the self that doesn’t get shown. Some room where the work happens before it becomes work that’s seen. They found a way to keep the window open even while the mirror was running.

The poet Mary Oliver lived this way. Famously private, allergic to self-promotion, she spent most of her life in relative obscurity before becoming one of the most beloved poets in America. She didn’t build a platform. She built a practice. Every morning, walking in the woods with a notebook, paying attention to things that would never trend, writing poems about geese and grasshoppers and the ordinary astonishment of being alive. When asked about her process, she said something I think about constantly: “Attention is the beginning of devotion.” Not attention as content generation. Attention as a spiritual practice. Attention as a way of being in the world that has nothing to do with being seen.

Or maybe they’re performing too, and they’re just better at it than I am. Maybe the authentic voice is always a construction, and the only difference is how visible the seams are. I don’t know. I genuinely don’t know.

What I do know is that I’ve started to want something different. Not instead of what I have. I’m not trading one identity for another. But alongside it. A life that isn’t entirely legible. Thoughts I don’t complete. Experiences I let dissolve without capturing them. The freedom to be uninteresting sometimes, to be ordinary, to have nothing to report.

It sounds simple. It’s not. The muscle memory runs deep. Even now, writing this, I can feel myself shaping it. Is this vulnerable enough? Is this too vulnerable? Does this land? Will this resonate? The audience is in the room. The audience is always in the room. I don’t know how to make them leave.

Maybe I start by admitting they’re there.

Have you heard of the “observing ego?” It’s the part of the self that watches the self, that maintains a slight distance even during intense experience. It’s supposed to be healthy, a sign of integration, the thing that keeps you from being completely swept away by emotion. But I wonder if the internet has hypertrophied this function. The observing ego has become the performing ego. It doesn’t just watch and reflect. It curates and broadcasts. The distance that was supposed to protect us has become the distance that alienates us from our own lives.

How do you collapse that distance? How do you get back inside your own experience?

I don’t have an answer. But I have some hunches.

The Shift

I don’t have a transformation to offer you. No five-step programme for recovering from interestingness, no morning routine that rewired my brain, no revelation that changed everything. That would, anyway, be another performance. The performance of having figured it out, which is maybe the most seductive performance of all.

What I have instead is something smaller. A reorientation. A slight turning of the head.

I’ve started letting things go. A book I loved that I didn’t tell anyone about. A thought that came to me in the shower and dissolved before I could capture it. A whole Tuesday where nothing happened that was worth narrating. I used to feel a low hum of guilt about these, a sense that I was wasting material. Now I’m trying to see them as something else. Proof that I still exist when no one is watching. Proof that there’s still a me that isn’t made of content.

There’s a difference between privacy and secrecy that I’m only now learning to articulate. Secrecy is about hiding something shameful. Privacy is about choosing what to share. For years I conflated these. If I wasn’t sharing something, it felt like I was hiding it, which meant there must be something wrong with it. But that’s not right. Some things aren’t hidden. They’re just held. They belong to you in a way that doesn’t need to be proven by making them visible to others.

The dal videos aren’t a secret. The comfort novels aren’t shameful. The crying at dog videos isn’t something I need to ironise or explain. They’re just private. They’re the rooms in my house where guests don’t go. Not because the rooms are dirty, but because some spaces are just for living in, not for showing.

I’ve also started paying attention to what interests me when no one’s looking. Not what I want to be interested in, not what would be interesting to be interested in, but the actual texture of my attention when it’s left alone. It’s different than I expected. Softer. Less impressive. More prone to the ordinary and the sentimental and the genuinely uncool.

It’s harder than it sounds. The instinct to capture is so deep now that resisting it feels almost physical. I’ll have an experience and feel my hand reach for my phone and have to consciously stop, consciously stay in the moment, consciously let it be unrecorded. Sometimes I manage it. Sometimes I don’t. The muscle memory is patient and I am only starting to build the counter-muscle.

I’ve started experimenting with what I think of as attention hygiene. Small practices, nothing dramatic. Not sharing something for forty-eight hours after I encounter it, to see if it still matters when the dopamine of novelty has faded. Keeping a google doc that isn’t for anything. No essays will come from it, no tweets, no reading list annotations. Just observations that dead-end. Thoughts that go nowhere. The stuff that would get cut from the highlight reel.

Reading things I know I’ll never reference. Watching films I’ll never review. Having conversations I won’t reconstruct later for someone else’s benefit. It sounds simple but it’s a kind of training. Teaching myself that experiences can be complete without being captured. That the tree can fall in the forest.

There’s a version of curiosity that isn’t about accumulation. I’m trying to find my way back to it. The kind where you look at something and don’t immediately think about what it means or how it connects or what you’ll do with it. You just look. The thing is itself and you are yourself and for a moment the transaction is complete without anyone else needing to witness it.

I used to think being interested was the input and being interesting was the output. The natural flow of a mind engaging with the world and then sharing what it found. I don’t think that’s wrong exactly, but I’ve started to wonder if the arrow can point the other way. If sometimes you have to protect the input from the output. If the sharing, done too automatically, starts to shape and eventually starve the thing it’s sharing.

I want to be interested in a way that doesn’t need to become interesting. I want to read without scouting. I want to think without drafting. I want to let some things stay half-formed, unresolved, not ready for an audience, maybe never ready for an audience. I want to have experiences that don’t become stories.

I want to sit in the car a little longer.

This essay is a contradiction, I know. I’m telling you about wanting to stop telling you things. I’m making my desire for privacy public, performing my exhaustion with performance. The irony isn’t lost on me. Maybe that’s the last thing I need to accept, that I can’t write my way out of this. The writing is part of the trap. The window becomes a mirror the moment you describe the view.

But I’m going to try anyway. Not to stop being interesting, I don’t think I know how to do that, and I’m not sure I want to. But to hold it more loosely. To let there be a gap between the experience and the narration. To remember that I exist even when I’m not producing evidence of existing.

Weil wrote that attention is a form of prayer. I’m not particularly religious, but I think I understand now what she meant. There’s a way of being present that doesn’t take. That doesn’t extract. That doesn’t turn the moment into material. It just witnesses, and the witnessing is enough.

I’m not there yet. I may never be. The audience is still in the room. But I’m learning to let them wait. Learning that not everything needs to be served. Learning that some attention is just for me. Formless, purposeless, unremarkable.

To be, sometimes, just a person in a stationary vehicle.

Listening to nothing.

Going nowhere yet.

To me, the demand to be interesting is really the demand to communicate meaning through Storytelling which will be the biggest buffer skill in the current AI shift.

Is there a experience without experiencer??

- from who is performing to ask better questions 🥲