And. But. Enough.

How language writes us into double bind, and how we can rewrite the rules.

He’s a father, but he travels a lot for work.

He’s a great partner, but he forgets anniversaries.

He’s a dedicated leader, but he loses his temper sometimes.

That “but” is a magic word. It erases tension. It excuses contradiction. It lets men stay whole in the public imagination, even when parts of them are in direct conflict. They’re allowed to be competent professionals but mediocre dads. Loving fathers but terrible husbands. Generous bosses but inconsistent friends. The “but” keeps them intact.

Women rarely get “buts.” We are forced into “ands.”

She’s a mother and a professional and a daughter and a wife and a sister and a friend.

The list never ends. The performance never stops. The “and” is a chain.

And if you try to step off the chain? You’re punished. Be a “but” woman, “she’s a good mom but not ambitious” or “she’s a dedicated professional but not very maternal”, and suddenly you’re a failure. Collect every “and” you can, and people call you distracted, scattered, unfocused. Either way, you lose.

I didn’t have language for this at first. Just a burn of recognition whenever I saw how men and women were described. A male colleague who stayed late was praised as “a family man, but he works so hard.” A woman who left at 6:30 to pick up her child was branded “less committed.” She was a mother and an employee, and therefore never enough of either.

It shows up in families too. A man who sends money home is a good son, even if he forgets to call. A woman must send money and call and remember birthdays and show up at weddings and be polite about it.

The words “and” and “but” are doing invisible labor. They decide who gets to be complex and who must be seamless. Men are allowed contradictions. Women are asked to reconcile contradictions until they collapse.

I think of the women I know, friends, cousins, colleagues, who never stop listing the things they do. “I’m a manager and a daughter and the one who handles the family WhatsApp group and the one who renews my parents’ health insurance and the one who coordinates dinner plans.” Nobody ever says of them, admiringly, “She’s a good daughter but sometimes she drops the ball.” Dropping the ball is not permitted.

Meanwhile, men’s contradictions get spun into charm. A man can be “messy but brilliant.” A woman is “messy and irresponsible.” A man is “stubborn but principled.” A woman is “stubborn and difficult.” The “but” flatters him. The “and” condemns her.

This is a double bind in miniature. Feminist scholars have written for decades about how women can’t win: too ambitious and you’re unlikable, too soft and you’re incompetent. Work too much and you’re a bad mom; mother too much and you’re unserious. My “and vs. but” shorthand is just a way to show how that bind lives in our everyday language.

Look at how we describe leaders. Male CEOs are “visionary but impatient.” Female CEOs are “visionary and demanding and cold and somehow still not enough.” The man’s flaws are footnotes. The woman’s are the whole thesis.

Even in pop culture, the pattern screams. Hollywood dads are “absent but charming.” Hollywood moms are “present and exhausted and nagging and resented.” The dad who shows up at a soccer game once is a hero. The mom who shows up at every game, packs snacks, and coordinates carpools? She’s invisible. Nobody says, “She’s a great mom but she misses a few games.” That “but” never arrives to save her.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Every conversation, every obituary, every profile reads like a gendered ledger of conjunctions. Men’s humanity is cushioned by “buts.” Women’s humanity is buried under “ands.”

This framing is exhausting. It teaches women that being a full person is a liability. It teaches men that contradictions are charming. It keeps us locked in roles that serve no one. Because honestly, men deserve to be whole too. They deserve to be parents and professionals without a “but” that excuses absenteeism. Women deserve to be parents but also professionals without being called selfish.

At first, I thought: surely two conjunctions can’t explain the weight of centuries. But simplicity is the point. Patriarchy hides in plain sight, in the smallest words, in the most ordinary sentences. “And” and “but” are just the tip of the iceberg, but they give us a vocabulary for the trap so many women feel without being able to name.

That’s what this essay is about. Naming the trap. Tracing its history. Showing the data. Pulling the receipts. And then asking: what would it mean to step out of the “and” prison and claim the “but” freedom?

Until we do, women will keep drowning in “ands” while men float on “buts.” And I, for one, am tired of drowning.

The Linguistic Trap

We underestimate the power of small words. Conjunctions don’t look like power tools. They’re glue words, connective tissue. Which is why they’re so sneaky. Inside those two or three letters lies an entire worldview.

Take “but.” In linguistics, “but” is a contrastive conjunction. Its job is to set up a contradiction and then resolve it. “He’s messy but brilliant.” You walk away remembering the brilliance, not the mess. “But” is a magic eraser. It acknowledges tension and then flips the spotlight to whatever comes after.

“And” works differently. It’s additive. It doesn’t excuse or explain; it piles on. “She’s a great mom and a serious professional and she runs marathons.” Instead of resolving contradictions, “and” compounds them. It creates a checklist, a burden, a sense of infinity.

In our culture, men are more often described with “buts,” women with “ands.” This is not random. It’s gendered framing doing heavy lifting.

Think of obituaries. Male leaders: “He was a hard-driving businessman but a devoted family man.” Female leaders: “She was a pioneering scientist and a mother of three and a mentor to countless students.” One reads like a redemption arc. The other reads like an overstuffed résumé.

Even in casual talk, the pattern holds. “He’s a terrible texter but he’s a good guy.” “She’s smart and pretty and nice.” He gets contradictions erased. She gets expectations stacked.

Language isn’t neutral. As cognitive linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue, the metaphors we live by, the tiny linguistic patterns we repeat, literally shape how we think. If men are habitually described with “buts,” we’re trained to overlook their flaws. If women are habitually described with “ands,” we’re trained to measure them against an endless to-do list.

It’s why a dad who forgets to pack school lunch gets praised for showing up at the PTA meeting (“he’s busy, but he cares”), while the mom who does both is invisible. His “but” makes his contradiction tolerable. Her “and” makes her obligations invisible until they’re incomplete.

Celebrity profiles prove the point. Men get contradictions made charming: the bad boy but family man, the ruthless CEO but humble dad. Women get multiplicities turned into burdens: Serena Williams is the GOAT athlete and a mother and a businesswoman and still critiqued for being “too emotional.” Beyoncé is the most decorated artist in Grammy history and a wife and a mogul and still scrutinized for every slip. Their contradictions don’t get softened; their achievements get stacked until they topple.

In academic terms, this is called markedness. Men are treated as the unmarked default, their flaws glossed over. Women are the marked category, with everything itemized and scrutinized. The conjunctions mirror that dynamic.

And the trap doesn’t just shape how others describe us, it shapes how we describe ourselves. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve stacked “ands” to prove I’m holding it all together. Meanwhile, I’ve watched men introduce themselves as “but” people: “I’m not great with details, but I think big picture.” The “but” softens and rebrands. The “and” exhausts and condemns.

Cognitive psychologists would call this a framing effect. “But” frames negatives into afterthoughts. “And” gives every demand equal weight. In a gendered world, that neutrality becomes punishment. Women’s contradictions aren’t erased; they’re spotlighted alongside every other responsibility.

Once you tune into it, the imbalance is everywhere. Corporate bios. Award show intros. Family WhatsApp groups. Men as “buts.” Women as “ands.” It’s death by conjunction.

Which raises the question: how did we get here? Why are women chained to “and” while men float on “but”?

The answer isn’t just about words. It’s about history. The second shift. The supermom myth. The cultural script that told women they had to do everything at once.

That’s where we go next.

Historical Roots

The “and vs. but” trap didn’t appear out of thin air. It’s the byproduct of centuries of gender scripts that taught men to be specialists and women to be generalists. Men were allowed to be one thing at a time. Women had to be everything at once.

The Separate Spheres

In the 19th century, Western societies ran on the “separate spheres” ideology. Men belonged to the public sphere: work, politics, money. Women belonged to the private sphere: home, children, morality.

This created the first “but privilege.” A man could be ambitious but absent at home, his breadwinner role excused it. A woman could never claim such a clause. She was expected to be daughter and wife and mother and homemaker, without dropping a single layer. Failure wasn’t just personal; it was framed as moral collapse.

Industrialization and the Superwoman Myth

World wars pulled women into factories and offices, but domestic duties didn’t vanish. Rosie the Riveter was the perfect propaganda poster: she could build planes and cook dinner and raise kids and keep the house clean.

By the 1950s, the suburban ideal had mothers like June Cleaver on TV: endlessly patient, endlessly available. Fathers could be tired but respectable. Mothers had no such cushion. They had to be everything at once.

The feminist movements of the 60s and 70s cracked open opportunities, but instead of dismantling the “ands,” society just added more. You could be a professional now, but you still had to run the household. The superwoman myth of the 80s packaged it as empowerment: glossy magazines promising women they could “have it all”: career and kids and perfect hair.

Sociologist Arlie Hochschild named the scam in 1989. In The Second Shift, she documented how even in dual-income households, women worked an extra “shift” at home. Cooking, cleaning, managing schedules. Men could clock out and still be seen as good dads. Women had to clock out and clock back in at home.

That research gave academic teeth to what women already knew: being an “and” wasn’t optional, it was compulsory.

The Motherhood Penalty vs. Fatherhood Bonus

By the 2000s, data confirmed the linguistic trap. Amy Cuddy, Susan Fiske, and Peter Glick showed how working mothers were seen as warmer but less competent, while working fathers gained warmth without losing competence.

Economists call this the “motherhood penalty” vs. “fatherhood bonus.” Women’s earnings drop after having kids. Men’s often rise. He gets credit for showing up once. She gets judged for not showing up everywhere.

The Lean-In Era

The 2010s promised empowerment through ambition. Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In mantra urged women to sit at the table, claim leadership, and stop holding back. But it ignored structural barriers: no affordable childcare, no universal leave. What it really demanded was more “ands.” Be a boss and a mother and a partner and a volunteer. Do it all, and don’t let them see you sweat.

Men didn’t face equivalent pressure. They were still allowed “buts.” Aggressive but effective. Brilliant but eccentric. Their contradictions became part of their legend. Women’s became liabilities.

Today: Hustle Meets Care

In the 2020s, hustle culture collided with intensive parenting. Women are told to be ambitious professionals and emotionally available parents and wellness gurus and socially conscious citizens. Instagram moms must post Montessori play ideas, manage careers, track meal prep, and look grateful while doing it.

Men? Still cushioned by “buts.” The dad who forgets a recital is “busy but loving.” The mom who forgets is “busy and careless and failing.”

Globally, women perform 2.8 more hours of unpaid domestic work per day than men. In India, the gap is closer to five hours. In Japan, “matahara” (maternity harassment) penalizes women for pregnancy. In the U.S., mothers earn about 70 cents to a father’s dollar after kids. The “and” is universal. The “but” is male privilege disguised as nuance.

The Inheritance

This is what we’ve inherited: a history that taught women to stack “ands” without complaint and men to skate on “buts” without consequence. Every generation repackaged it but the root pattern never broke.

Which brings us here, to this essay, to this naming. Because once you see the trap, you start noticing it everywhere: in research, in statistics, in the words we use daily.

That’s where we go next: into the receipts.

The Research & The Data

I don’t want this to sound like just a rant you nod at because it feels true. I want you to know it is true.

Work–Family Conflict Isn’t Neutral

Studies consistently show that working mothers report higher levels of work–family conflict than fathers. Not because they care more, but because they’re expected to care more. Even in dual-income households, women shoulder the bulk of the “second shift.”

Hochschild’s landmark study in the 1980s showed women were effectively working an extra month of 24-hour days per year compared to their husbands. Forty years later, the gap hasn’t closed enough. Globally, women still perform 2.8 more hours of unpaid labor per day than men. In India, it’s closer to five. In the U.S., mothers spend about twice as much time on childcare as fathers.

Even when dads “help,” moms are usually the default managers: the ones who carry the mental load of remembering, scheduling, anticipating. Sociologists describe this as: he’ll do the chore, but she’ll remember it needs doing. That hidden “and” means she’s never off duty.

Judgment Is Gendered

Pew Research found that more than half of Americans believe mothers today are doing worse than previous generations. Less than half said the same about fathers. Translation: women are judged against a harsher benchmark.

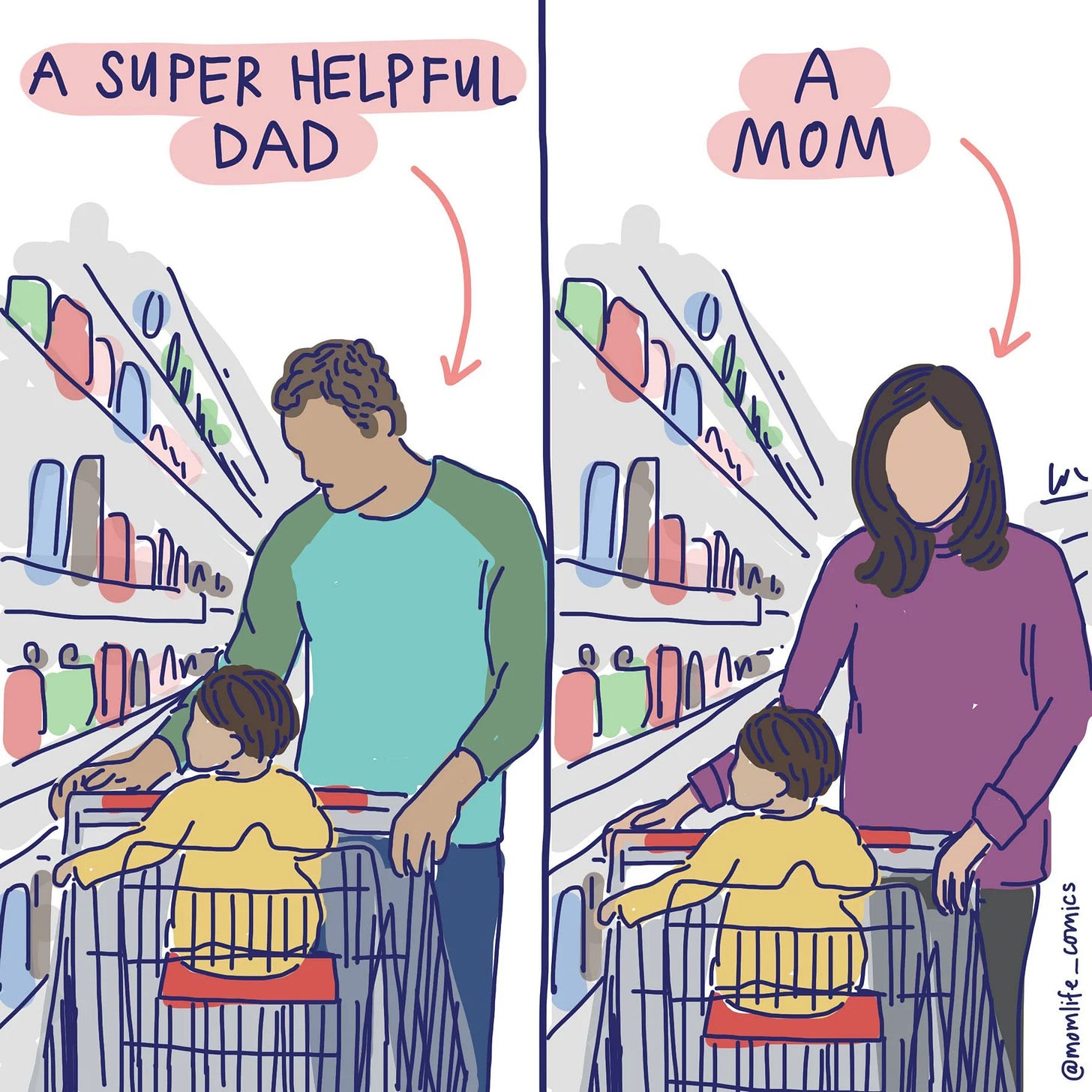

It plays out in daily life. A father missing a school play is “busy but loving.” A mother missing the same play is “busy and neglectful.” A dad who cooks once a week is “hands-on.” A mom who cooks six nights and orders pizza on the seventh is “lazy.”

Cartoonist Mary Catherine Starr nailed this dynamic in her viral “mom vs. dad” comics: Dad makes dinner once, and he’s a hero. Mom makes dinner every night, and it’s invisible. Those comics resonated because they illustrated the linguistic trap as lived reality.

Leadership and the Double Bind

The same pattern haunts workplaces. Social psychologists call it the double bind of female leadership: women must appear both competent and warm, assertive and likable. Men are free to pick one side of the coin.

Catalyst, a nonprofit that studies women in leadership, sums it up: “Men are free to be both competent and liked. Women must constantly prove they can be both, and are punished if they lean too hard in either direction.”

Men are “brilliant but abrasive.” Women are “brilliant and abrasive.” The “but” neutralizes his flaw. The “and” compounds hers.

The Motherhood Penalty vs. Fatherhood Bonus

Economists have quantified this in the workplace. Mothers experience an average 4% wage loss per child, a phenomenon known as the motherhood penalty. Fathers often experience a fatherhood bonus: higher pay and greater perceived stability once they have kids.

The logic is chilling in its simplicity: he has a family, but he’s still ambitious. She has a family, and therefore she must be less ambitious. His “but” protects him. Her “and” punishes her.

Emotional Labor and the Mental Load

Beyond wages, women are asked to manage the invisible glue of workplaces and families. Hochschild called this emotional labor, the work of managing other people’s feelings. At home, it’s evolved into the concept of the mental load: anticipating needs, remembering birthdays, soothing egos, smoothing conflicts.

Research shows that even in so-called egalitarian households, mothers carry the mental labor of childcare. Fathers may participate in tasks, but mothers remain the project managers. She’s expected to coordinate, delegate, thank, and still execute. He’s expected to “help.”

That hidden “and” explains why women report higher levels of burnout even when the visible division of chores looks balanced. It’s not just what gets done. It’s who remembers and worries about it.

The Toll on Women

The psychological cost is staggering. Women report higher guilt levels when they fall short in either work or family. Researchers call this “role overload”: the feeling of failing everyone at once.

A 2022 Pew survey found 66% of mothers said parenting is harder than they expected, compared to 58% of fathers. More than half of mothers said they feel judged regularly about their parenting, versus about a third of fathers.

This isn’t just about feelings. It shapes careers. Women scale back ambitions, decline promotions, or leave the workforce entirely because the “and” trap is unsustainable. Men rarely face the same pressure. When they do, it’s often framed as noble sacrifice: “choosing family over work.” When women step back, it’s treated as deficiency.

Why Naming Matters

This is why the “and vs. but” theory isn’t just a metaphor, it’s a diagnostic. Men are granted contradictions as quirks. Women are forced to carry multiplicities as obligations.

He’s late but dedicated. She’s late and irresponsible.

He’s messy but brilliant. She’s messy and careless.

It’s not just semantics. It’s salaries. It’s stress. It’s survival.

Pop Culture Mirrors

Culture doesn’t invent gender roles out of nowhere, it reflects and amplifies them. If you want proof of the “and vs. but” trap, you don’t need academic journals. Just turn on the TV.

Sitcom Dads vs. Sitcom Moms

Think of sitcom dads: Homer Simpson, Phil Dunphy on Modern Family, Dan Conner on Roseanne. They’re bumbling, forgetful, lazy but lovable. Their flaws are the joke, their affection the redemption arc.

Now the moms: Marge Simpson, Claire Dunphy, Roseanne. They’re competent, patient, endlessly juggling. When they falter, it’s not charming. It’s shrill, nagging, or failure. He gets a “but” that excuses him. She gets “ands” that bury her.

Celebrity Profiles

Open a glossy magazine. Male celebrities are contradictions made charming:

“He’s a bad boy but a family man.”

“He’s eccentric but a genius.”

“He’s ruthless but visionary.”

Women, by contrast, are lists of “ands”:

Beyoncé is a performer and a mother and a mogul and still policed for not being “relatable enough.”

Serena Williams is the greatest athlete alive and a mother and a businesswoman and critiqued for being “too emotional” on court.

The “but” flatters men into complexity. The “and” loads women with obligation.

Movies That Subvert the Trap

Sometimes culture pushes back. Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) put Evelyn Wang, a middle-aged immigrant mom, at the center of a multiverse epic. The film literalized what being a woman feels like: living a thousand lives at once, across infinite timelines, while still doing laundry. Evelyn isn’t defined by one contradiction. She’s forced to be every version of herself and keep the family together.

Critics called it “chaotic” and “unrelenting.” Of course they did. That’s what being an “and” feels like. But the film made her burden heroic. She wasn’t a footnote in a man’s redemption arc, she was the story.

Contrast that with male blockbusters, where one “but” defines the myth: Batman is tortured but just. Iron Man is arrogant but brilliant. James Bond is violent but suave. Men get one clause of redemption. Women get endless clauses of demand.

Influencer Culture

Instagram has turned motherhood into a performance of “ands.” Momfluencers post homemade Montessori toys, organic snacks, career tips, fitness routines, and gratitude captions. The algorithm rewards multiplicity. If you’re not doing all of it, you’re doing none of it.

Dadfluencers thrive on the opposite. One post of baby-wearing or making pancakes floods with “What an amazing father!” Their contradictions, business trips but bedtime stories, are celebrated as balance. Women’s multiplicities? Baseline expectation.

The Ledger

Here’s the pattern in one sentence: men’s flaws are softened into quirks by “buts.” Women’s achievements are flattened into burdens by “ands.”

The sitcom dad who forgets the milk is “a mess but lovable.” The sitcom mom who forgets the milk is “a mess and failing.” The celebrity dad who’s late is “busy but dedicated.” The celebrity mom who’s late is “busy and neglectful.”

Culture doesn’t just reflect this trap—it trains us into it. We laugh at bumbling dads. We roll our eyes at “nagging” moms. We cheer men’s contradictions. We grind women into “ands.”

And because culture is how we learn what’s normal, the trap seeps back into workplaces, politics, families. If you’ve grown up on dads cushioned by “buts” and moms smothered by “ands,” of course you’ll judge the woman who leaves at 5 p.m. for daycare more harshly than the man who stays late.

Pop culture is our collective subconscious. It teaches us who gets excused and who gets exhausted. And until we change those stories, women will keep drowning in “ands,” while men float on “buts.”

The Personal Reckoning

The hardest part of writing this is realizing how much of the “and” trap I’ve swallowed whole. It isn’t just something I spot in sitcoms or research papers, it’s how I narrate my own life.

I’ve always described myself in “ands.”

I’m running a fund and writing a book and keeping up with family obligations and trying to be a decent friend and going to the gym. The word sits in my head like a whip: add more, add more, add more.

And when I drop one? I feel defective. Like the whole tower of “ands” comes crashing down, no matter how high I’ve stacked it.

Meanwhile, I’ve watched men frame themselves in “buts.” I once sat in a meeting where a male colleague said, almost proudly, “I’m not great with details, but I think big picture.” Everyone nodded like it was charming. When I’ve admitted to slipping, I don’t get a soft landing. I get more “ands” piled on: and she’s too distracted, and she’s stretched too thin, and maybe she’s not serious enough.

It’s in families too. Male cousins are “scatterbrained but brilliant.” Female cousins are “scatterbrained and unreliable.” Same trait, different conjunction: one redeems, the other condemns.

Sometimes I’ve tried to be a “but” woman. I’ve said, “I’m ambitious, but I’m not the most domestic.” Or, “I’m committed to my work, but I may not make every family function.” The backlash was instant. Silence, raised eyebrows, the unspoken accusation: selfish, careless, ungrateful.

That’s the bind. Claim a “but,” you’re punished. Submit to the “ands,” you’re exhausted.

The cruelest part is how invisible it becomes. You convince yourself it’s just adulthood, just ambition, just being a woman. You tell yourself you chose it. But deep down, you know the choice was scripted for you.

I think of nights I’ve stayed up past midnight, toggling between a draft, checking in on my parents, replying to founders, setting alarms for the gym. Nobody asked me to hold all those “ands.” But if I dropped even one, someone would notice. Someone would call me out. And worse, I’d call myself out.

We don’t just perform the “ands” for others, we police them in ourselves. We’ve learned to mistrust our own “buts.”

And what does that do? It makes us smaller. It makes us tired. It convinces us that rest is laziness, that boundaries are betrayal, that choosing one role over another is failure.

I look at men who live freely inside their contradictions, and sometimes I feel rage. He’s late but brilliant. He’s messy but lovable. He’s distant but successful. Why don’t women get that clause? Why don’t we get the right to be incomplete without being defined as failures?

That’s why I keep returning to this theory. It explains why so many women feel like they’re constantly failing, even when they’re doing everything. Why guilt is the background music of our days.

Naming the trap doesn’t fix it. But it makes it visible. And once you see it clearly, you can ask new questions:

What would it mean to live as a “but” woman? To say, “I’m a good friend but I don’t always reply instantly.” “I’m ambitious but I need rest.” “I’m a daughter but I have limits.”

And what would it mean for men to carry more “ands”? To say, “I’m a father and I cook and I manage the school calendar and I show up emotionally.” To stop being cushioned by contradictions and start sharing multiplicity.

I don’t have the neat answer. But I know this: I’m tired of drowning in “ands.” I want the grace of a “but.”

Call to Action / Reframe

So what do we do with this theory of “and vs. but”?

First, we name it. Language isn’t decoration, it’s architecture. Those tiny conjunctions decide who gets forgiven and who gets flattened. If we keep letting men live in “buts” while women drown in “ands,” the trap will keep replicating itself in workplaces, families, politics, everywhere.

Second, we demand redistribution. The grace of contradiction shouldn’t be a male-only luxury. Women deserve “buts” too:

She’s ambitious but she doesn’t answer emails after 7.

She’s a loving mother but she hates the PTA bake sale.

She’s a great leader but she’s blunt.

Those “buts” don’t erase worth, they humanize it. They let us be full people, not robots powered by infinite “ands.”

At the same time, men need more “ands.” Enough with the soft landings. Fatherhood should not be a part-time gig with applause for pancake duty. Caregiving, scheduling, remembering, tending, the invisible “ands” must be shared. He’s a breadwinner and a parent and a partner and a friend. Let him feel multiplicity too.

What Needs to Shift

Culturally: Rewrite the stories. Stop laughing at bumbling dads as lovable exceptions. Stop treating multitasking moms as invisible baseline. Celebrate women’s contradictions as depth, not failure. Expect men’s “ands” as normal, not heroic.

Structurally: Policy matters. Paid paternity leave. Affordable childcare. Real workplace flexibility. Until men are invited into “ands” structurally, women will keep carrying the load. Until mothers aren’t penalized for every slip, “but” won’t stick to us.

Personally: Change the grammar inside yourself. Notice when you stack “ands” like badges. Notice when you deny yourself a “but.” Try saying: “I’m good at my job but I need breaks.” “I love my family but I have limits.” Feel how freeing it is.

The Reframe

Imagine a world where women are allowed contradictions without collapse, and men are asked to carry multiplicity without applause. Where “but” is not an escape hatch but a balancing act. Where “and” is not a sentence but a shared responsibility.

That’s the shift. It isn’t just swapping words. It’s redistributing humanity. Giving everyone the right to be messy, flawed, complex, forgiven.

Because this about who gets to be fully human. Who gets to be competent and complicated. Who gets the luxury of imperfection.

I want that luxury. I want the grace of “but.” I want the relief of knowing I don’t have to carry every “and” alone. And I want a world where when I drop a ball, the sentence doesn’t end with failure, it continues with forgiveness.

We deserve that. All of us.